|

|

|

HOME > FOCUS > Seventy Years of Sculpture at The Museum of Modern Art, Kamakura & Hayama |

|

|

Focus features two in-depth reviews each month of fine art, architecture, and design exhibitions at art museums, galleries, and alternative spaces around Japan. |

|

|

|

|

|

Seventy Years of Sculpture at The Museum of Modern Art, Kamakura & Hayama

Susan Rogers Chikuba |

|

A sculpture garden with beach access is a bonus attraction of The Museum of Modern Art, Hayama. Nestled between the Sangaoka hills and the Isshiki coast of Sagami Bay, the museum is next door to Hayama Shiosai Park (the former Hayama Imperial Villa Annex), where you can stroll the traditional Japanese garden and order a cup of matcha tea to round out your visit. Photo by Jeff Amas

|

The Museum of Modern Art, Kamakura & Hayama is marking its 70th anniversary with Forms in Space: from Alberto Giacometti to Tadaaki Kuwayama, a showcase of some 90 contemporary sculptures from its formidable collection of hundreds. Concurrently, one gallery is given over to The Works of Isamu Wakabayashi: Donations from Takanori Kawai, a debut of holdings donated last year by a private collector and ardent fan of the late artist. These shows are at the museum's Hayama address, near Zushi Station an hour by train southwest of Tokyo.

Though rendered in cement, a go-to material of its day, Eye in the Hand (1955) by Bushiro Mori seems to flex with life. Photo by Jeff Amas

|

Forms in Space offers a rich mix of sculpture styles, materials, and sizes across the decades from the mid-century onward. Artists well-known to the Western world -- Alberto Giacometti, Isamu Noguchi, Marta Pan, the Dadaist Jean Arp, and kinetic specialist George Rickey -- are represented, but there is real value in familiarizing yourself with the host of Japanese sculptors past and present.

Some juxtapositions of these "forms in space" are sublime -- like the trifecta of Kazuo Yagi's ceramic Work (1963), Kiichi Sumikawa's wooden MASK (1975), and Yoshio Yoshida's bronze Actor G (Child) (1975) against a single wall, or the inspired unison of works by Ainu sculptor Bikky Sunazawa (1931-89) and land artist David Nash (b. 1945) in one corner entitled "Souls of Wood." A section that unites four who sought expression through painting as well as sculpting -- Arp (1886-1966), Giacometti (1901-66), Saburo Aso (1913-2000), and Chimei Hamada (1917-2018) -- is pure eye candy, presenting as it does their two- and three-dimensional attempts to transcend the stuff of our psychological experience.

|

|

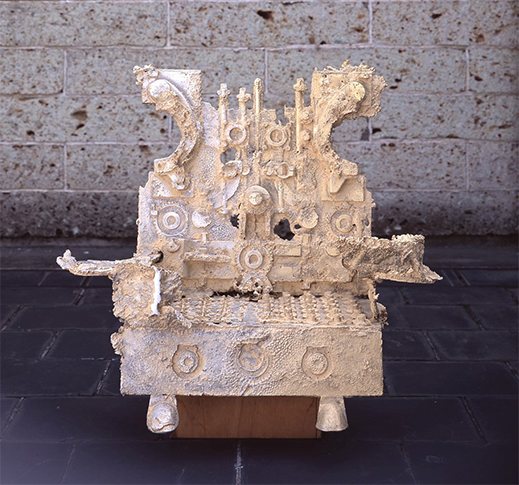

A satire on the notion of victory, Chair for Winner (1964) by Ryokichi Mukai was a response to the Olympic Games held in Tokyo that year.

|

Works by postwar dynamos Ryokichi Mukai (1918-2010) and Bushiro Mori (1923-2004) feature in a section themed on "emptiness and existence." Mori's archetypal Eye in the Hand (1955) recalls talismans found in northwest Africa, the Middle East, and even Mississippian indigenous cultures, while his abstract Nest of Pigeon, Based on the Ruins in Mexico (1959), a work in concrete, elicits reflections on the role of the organic and inorganic in constructions destined for decay. Mukai, meanwhile, renewed his intention to become a sculptor by carving an image of the bodhisattva Kannon (Avalokiteshvara) during his time in captivity as a prisoner of war in Papua New Guinea. In later years he spoke of the anarchic fatalism evinced by soldiers and others who have survived terror amid the meaninglessness of war. His Chair for Winner (1964) evokes the sorrow inherent in any worldly claim of glory. But all was not gloom in his career: Mukai is also the hand behind the curvy acoustic wall components in the main hall of Tokyo Bunka Kaikan -- those endearing organic beechwood forms that literally and figuratively amplify our concert experiences there, and define the space as much as does Kunio Maekawa's iconic 1961 architecture.

|

|

In works like A Dog In IV (1968), Isamu Wakabayashi considered our perception of physicality, and its dependence on defined boundaries. Kawai Collection, photo by Jeff Amas

|

The Isamu Wakabayashi (1936-2003) exhibits unite his multifarious sculptures with drawings, prints, and even New Year's cards he made from 1954 up to the year before his death. It is testimony to his versatility that the creative breadth on display by this single artist, in the first gallery one enters, serves as a fitting prelude to the exhibits of the main show.

Wakabayashi's world is one of deep contemplation of the inner self. He was concerned with perceived limitations of the body-mind and its relation to the whole that envelops it. His works might address, for example, the narrative of gaps and distances between subject and object, or consider the difference between symbols (the contents of our awareness) and awareness itself, which is non-symbolic. Throughout his prolific career he was thus looking at the dilemma of our species: to understand consciousness, we have to use the conditioned mind, itself a creation of consciousness at play.

|

|

If the title of this 1967 iron sculpture by Wakabayashi were not CANNIBAL II, would we interpret its facial features differently? Kawai Collection, photo by Jeff Amas

|

Some of Wakabayashi's works explore these themes from a spatial perspective, like those of his "A Dog Inside" series, or Model of the Measurement of the Space before My Eyes III. The sketches in A Branch of Dogwood, Cooling off and Heating up in July (1986) are fascinating for their portrayal of how the surroundings appear from minute vantage points on a tree. Still others, such as Smoke Tracks of a Burning Plane (10 x 10 VII) or the "Black Cotton" portfolio of lithographs drawn from a childhood memory of a cotton-mill fire, treat the transient nature of matter as it flows from solid state to liquid to gas and back again.

Wakabayashi's Smoke Tracks of a Burning Plane (10 x 10 VII) captures a memory of wartime -- his mind's eye seeing not the burning plane, but rather the trail of black smoke it became. Behind it is a lithograph from his "Black Cotton" portfolio. Kawai Collection, photo by Jeff Amas |

Wakabayashi turns up in the Forms in Space show, too, in a section that introduces the International Steel Sculpture Symposium held in Osaka in 1969. He and 12 other sculptors representing Japan, Austria, Germany, England, Scotland, Switzerland, and the United States participated in the three-month event, collaborating with factory workers and engineers to create 13 large-scale works that would be exhibited at Expo '70 the following year.

Among the archival photographs on display are those documenting the making of Wakabayashi's sunken sculpture Wings of a Blowfly 3.25 meters Long, one of just three of those original 13 works still in situ at the Expo '70 Commemorative Park. The insect's wings appear in relief on a five-by-eight-meter steel panel that rests on the ground, but this is just the surface of what is actually a meter-high box buried below. Tiny hinged doors suggest that we might peek inside to catch a glimpse of the giant fly that seemingly lurks beneath our feet, like the parable about blind men trying to conceptualize the whole of an elephant by touching only parts of its body.

|

|

The white bronze CRESCENT by Wakiro Sumi (b. 1950) was designed in 1991 and cast in 2002. Photo by Jeff Amas |

The 1969 photographs portray an era when men around the world had moved from the industry of war to civilian pursuits, and reveal the camaraderie enjoyed by the artists and steel engineers. For the factory workers these projects must have been a welcome departure from routine; for the artists, the three-month residency was an opportunity to hone or learn skills in handling steel for large-scale works. No longer scrapped for the war effort, metal was once again available for outdoor installations and sculpture exhibitions that would become an increasingly frequent feature of the art scene.

Hisayuki Mogami used traditional Japanese joinery techniques to show off the beauty of wood, as in Ton Ton Ton, Rhythm with Feet (1989). In the background is Northern King and Queen (1987), a carving by Ainu artist Bikky Sunazawa. Photo by Jeff Amas |

Another highlight of Forms in Space is the reinstallation of Ton Ton Ton, Rhythm with Feet (1989), a three-meter-high work by Hisayuki Mogami (1936-2018) last shown at a 2005 retrospective commemorating his retirement from teaching, and before that only at its 1989 Kamakura debut. If you've ever been to the Minatomirai complex in Yokohama, chances are you've seen his looping steel windbreak structure at Landmark Plaza. But Mogami's first and last love was wood, which he configured into modern abstractions of form using old-fashioned joinery techniques and principles of tension and compression.

Untitled (2004), an installation by Tadaaki Kuwayama, is given stand-alone treatment in a section of the show entitled "Exhibition Room as a Work of Art." Photo by Tadasu Yamamoto |

Featured in the next-to-last gallery is the work of Tadaaki Kuwayama (b. 1932), who moved from Japan to New York in 1958 and made a name for himself in the Minimalist movement of the 1960s and '70s, painting reductive canvases in bright swathes of color. Later he explored perceptual and spatial dimensions in more subtle ways -- as with his work on view at Hayama. When I first saw the above photograph before attending the show, I wondered what could be said of 22 plain white frames of identical size hung in perfect alignment on one wall of a white room. But to experience this installation is something else altogether. Closer inspection reveals that a single faint line runs horizontally across each frame, and that these are drawn in alternating colors of blue and red. That's all there is to see, but as our sight-centric faculties recede, much else comes alive: you notice the scent of the room, the temperature and flow of air currents on the skin, the hum of the lights and ventilation system, your own breath in the midst of it all. When the walls themselves drop away, who knows -- you might find yourself hovering outside where the waves lap the shore, seagulls ride the updrafts, and boats ply the shimmering water.

|

|

Koichi Ebizuka (b. 1951) plays with material-based conceptions of the elements in Cubic Measure of Water and Wind (2001), a work in weathered steel and cast iron. Photo by Jeff Amas |

It's remarkable that this prefectural institution was established just five years in to the postwar reconstruction effort. Its maiden building, completed in 1951 on the grounds of Tsurugaoka Hachimangu shrine in Kamakura, was Japan's first public museum for modern art. Designed by Modern Movement leader Junzo Sakakura (1901-69), who had worked under Le Corbusier in Paris, it closed its doors in 2016. Today the museum operates from two locations: a Kamakura annex built in 1984, and Hayama, just south of Kamakura and built in 2003 to store and display its vast holdings in a modern facility. With your senses primed after taking in so many iterations of line and form, step outside to stroll the wooded sculpture garden and see the natural world with fresh eyes.

Admission to both shows is included with the purchase of a ticket to Forms in Space. Entry is by reservation only, via the museum website. Little information on the artists and their works is provided in English, but a review of Wakabayashi's oeuvre can be found on artscape here.

All works shown are held in the collections of The Museum of Modern Art, Kamakura & Hayama, which generously granted photo permissions. |

|

|

Susan Rogers Chikuba

Susan Rogers Chikuba, a Tokyo-based writer, editor and translator, has been following popular culture, architecture and design in Japan for three decades. She covers the country's travel, art, literary and culinary scenes for domestic and international publications. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|