|

Focus features two in-depth reviews each month of fine art, architecture, and design exhibitions at art museums, galleries, and alternative spaces around Japan. |

|

|

|

|

|

Journeys of the Imagination: Mexico and Japanese Artists

Jennifer Pastore |

|

Koji Suzuki gives a painting demonstration at Ichihara Lakeside Museum. |

Japan-Mexico relations were first forged in 1609, when a ship headed to Mexico from the Philippines wrecked off the coast of Chiba. Now, more than 400 years later, Chiba's Ichihara Lakeside Museum takes a look at the cultural influence of Mexico on Japan in The Impact of Mexico: Mexican Experiences Shake Japan Radically. This exhibition explores how Mexico has shaped eight Japanese artists in a range of fields including painting, sculpting, conceptual art, and filmmaking.

Taro Okamoto

Photographs of Mexican ruins intrigued Taro Okamoto (1911−1996), a long-time student of anthropology. He first visited Mexico in 1963. His iconic mural Myth of Tomorrow (1968) is currently installed at Shibuya Station, but it was originally produced for Hotel de Mexico, a facility planned for the 1968 Mexico City Olympics. The hotel was never completed and the mural went missing until 2003, when it turned up in a Mexican suburb. Ichihara Lakeside Museum presents a 1/3-scale replica of Myth of Tomorrow, which features the vivid colors and skeletal motifs common to Mexican art in its depiction of the aftermath of the atomic bomb. Also on display are photographs from Mexico taken by Okamoto in 1967. Capturing the markets, suburbs, and ruins around the country, the images reflect Okamoto's enchantment with Mexico's vibrancy, history, and humanity.

Replica of Taro Okamoto's Myth of Tomorrow |

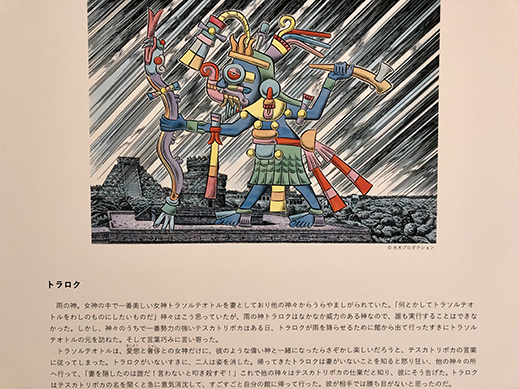

Shigeru Mizuki

Manga artist Shigeru Mizuki (1922−2015), famed for his portrayals of Japanese yokai spirits, was captivated with the otherworldly creatures of Mexico as well. In 1997 he spent two weeks travelling through the Oaxaca and Guerrero regions, where supernatural beliefs still thrived, witnessing Day of the Dead festivities. He also amassed an impressive collection of Mexican masks and later published the travelogue Shigeru Mizuki's Great Adventure: A Guide to the Happy Mexico -- Yokai Paradise. Along with drawings of Mexico's indigenous gods and mythical entities, examples from his mask collection are on display. "Mexico's masks stimulated my brain. They took forms I had never seen before . . . The Mexicans gave form to the formless. They are my predecessors," Mizuki wrote.

|

|

|

|

Above: Illustration of the Aztec rain god Tlaloc by Shigeru Mizuki. Below: From Shigeru Mizuki's collection of Mexican masks.

|

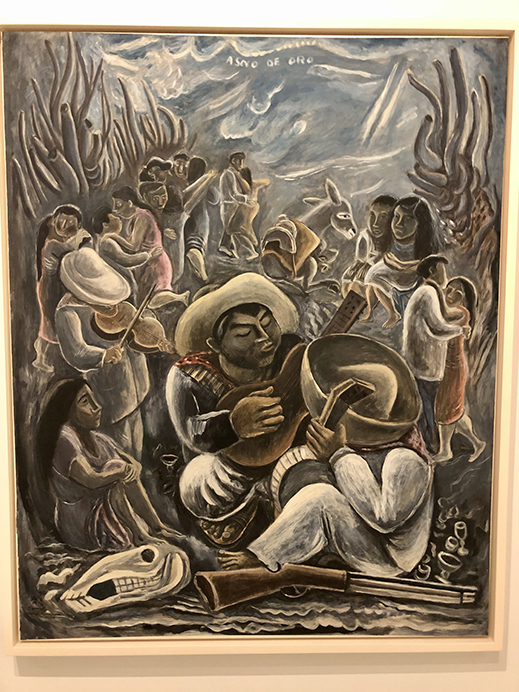

Tamiji Kitagawa

Tamiji Kitagawa (1894−1989) reached Mexico via New York and Cuba in 1921, at the conclusion of the Mexican Revolution. He participated in the Mexican Renaissance of the 1920s and 1930s, befriending its leaders Orozco, Rivera, and Siqueiros, and studying for a time with Frida Kahlo. Kitagawa produced paintings, lithographs, and murals, both during his 15 years in Mexico and after he returned to Japan in 1936. His style displays Japanese, European, and Mexican influences, with bold lines expressively depicting the lives of common people. Abounding in symbolism concerning Japanese and Mexican history, his work exemplifies the Muralist Movement belief that art should be for the masses while reflecting on social conditions. Kitagawa also engaged in art education for children in Mexico and served as headmaster for a plein-air school in Taxco. After returning to Japan, he opened the Kitagawa Institute of Children's Art in Nagoya and participated in prestigious events such as the Nikaten exhibition. In 1986 he was granted the Order of the Aztec Eagle, the highest honor bestowed on foreigners by the Mexican government.

|

|

Tamiji Kitagawa, Song of Ranchero (1938), The National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo. Kitagawa described this work as "a satirical portrayal of pre-WWII Japanese society."

|

Kojin Toneyama (1921−1994) came to Mexico later than Kitagawa, arriving in 1959 after taking inspiration from the pivotal 1955 Mexican Art Exhibition at the Tokyo National Museum. Toneyama was a painter, printmaker, and muralist who, like Kitagawa, sympathized with the ideals of the Mexican Renaissance. He became committed to socially engaged art practices after seeing a documentary on the Sakuma Dam. (The irony of showing his work at a museum adjacent to a lake created by the Takataki Dam should be noted.) His art incorporates motifs from ancient Mayan civilization, and rubbings he took from Mayan ruins are on display. His exhibition of Mayan frottages was held at the National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo and in Mexico City. After returning to Japan, he carried on in the tradition of the Muralist Movement, creating colorful, sculptural murals for Japanese public spaces. He was awarded the Order of the Aztec Eagle twice.

|

|

Kojin Toneyama, Mother and Child (1994), a mural that can still be seen across from Setagaya Park in Tokyo.

|

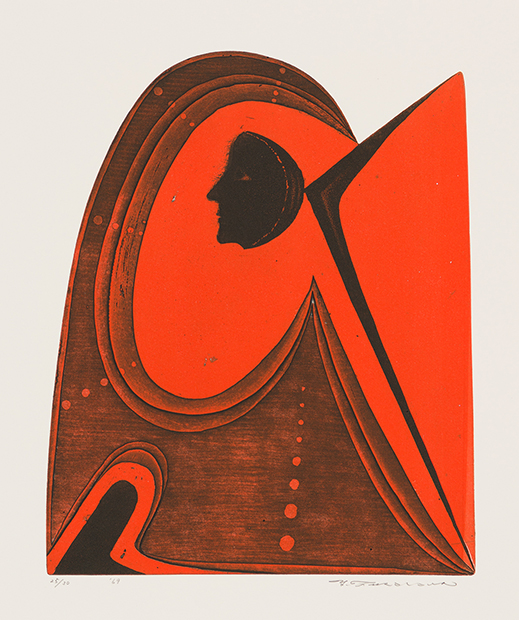

Yukio Fukazawa (1924−2017) was a pioneering printmaker invited to teach in Mexico in 1963. His copperplate printing techniques had a meaningful influence on the Mexican printing world, where woodblock printing had previously been the norm. Fukazawa was deeply impressed by Mexico's ancient ruins and began incorporating themes from Mexican culture and history in his works. Stunned by the strength of light and shadow in the country, he shifted away from monochrome palettes into colorful ones. During a second visit in 1974, travels in indigenous villages inspired him to begin a new series of works about prehistoric human migration from Asia across the Bering Strait. Fukazawa's works often seem Daliesque, with their abstract shapes combined with human forms and mysterious symbols. Their bright hues give them a modern edge. Fukazawa was awarded the Order of the Aztec Eagle in 1994. In homage to the artist, the rapper Dengaryu has co-produced a video called Mexico Seen by Yukio Fukazawa that can be viewed at the exhibition.

|

|

Yukio Fukazawa, Journey to Aztec (1969), Ichihara Lakeside Museum Collection (photo by Ichihara Lakeside Museum).

|

On Kawara

On Kawara (1932−2014), one of Japan's greatest conceptual artists, was also moved by the Mexican Art Exhibition, remarking, "For many modernists who have expressed the exaltation of humanity or freedom with the rigid abstract principles of Western Europe, nothing is more amazing than this exhibition." Kawara spent the years of 1959 through 1962 in Mexico; however, there is little documentation of what he did there during this time. After launching Date Paintings, a nearly five-decade-long series meditating on single calendar dates, Kawara returned to Mexico in 1968 and started a similar line of works, I Got Up (1968−1979). On each postcard in the series, Kawara records just the time he awoke that day. The exhibition displays dozens of these existential works, which on the front show standard tourist images of Mexico and on the back are addressed to the curator Kasper Konig, his friend and benefactor.

Mexican postcards from On Kawara's I Got Up series (1968−1969).

|

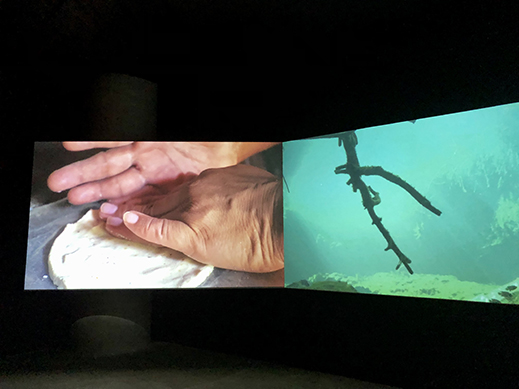

Kaori Oda

Kaori Oda (b. 1987) is an up-and-coming filmmaker who has studied and worked in the U.S., Bosnia, and Mexico. Her award-winning films have been screened at festivals in Japan and abroad. Ichihara Lakeside Museum presents her three-screen installation Day of the Dead (2021), a nearly 12-minute work she produced as part of a research trip in Mexico that resulted in her latest feature-length film, TS'ONOT/Cenote (2019). Day of the Dead documents a family in a small village as they gather, pray, and prepare a meal for the Day of the Dead. This portrayal contrasts with the common impression of the holiday as an exuberant celebration. Images of the family going about its day are interspersed with underwater shots from cenotes, the limestone reservoirs of the Yucatan where this world and the netherworld are said to connect in Mayan belief. Also on display are 38 paintings from Oda's muse series (2017−2018), a collection of 100 oil paintings of girls' faces adorned with beads and resin. Oda created the series as an "offering" to the cenotes.

|

|

From Kaori Oda's Day of the Dead (2021).

|

Koji Suzuki

Picture book artist Koji Suzuki (b. 1948) has been to Mexico eight times since the mid-1990s, when the Day of the Dead sparked his interest in the country. Many aspects of the culture certainly seem to align with his lively, maximalist style. "My pictures are all like Mexico. The jumbles of people, animals, skeletons, spirits, music, and festivals in my creative world all express a Mexican spirit," he says. Suzuki has manifested this energy in a room-spanning installation called VIVA! MEXICORAZON! From floor to ceiling, hundreds of new and previous paintings and sculptures, depicting people and creatures real and imagined, living and dead, fill the room in a vibrant burst of color and creativity. The motifs could easily come from Mexican folklore or one of Suzuki's picture books. An exhibition in and of itself, the display resembles a home-thrown, Mexico-themed party with no decoration spared.

Koji Suzuki, VIVA! MEXICORAZON! (2021), installation view.

|

With 2021 marking the 200th anniversary of Mexico's independence from Spain, now may be a good time to reassess the nation's cultural impact. As seen with these eight artists, Mexico has been a powerful source of inspiration. For roughly a century, Japanese creatives have been drawing from its history, mythology, people, and landscapes in their work. They have explored the country's unique understandings of life and death, antiquity and modernity, sacredness and profanity, and realism and surrealism. Sometimes they have used Mexico as a mirror to hold up to their own culture, and at other times they have charted entirely new artistic courses. Let's hope this cross-cultural conversation continues to flourish.

All photographs by Jennifer Pastore, courtesy of Ichihara Lakeside Museum, except where otherwise noted.

|

|

|

Jennifer Pastore

Jennifer Pastore is a Tokyo-based art fan and translator. In addition to Artscape Japan, her words have appeared in ArtAsia Pacific, Sotheby's, and other publications. She is an editor at Tokyo Art Beat.

|

|

|

|