|

Focus features two in-depth reviews each month of fine art, architecture, and design exhibitions at art museums, galleries, and alternative spaces around Japan. |

|

|

|

|

|

Cutting through the Mystery of Japanese Swords

J.M. Hammond |

|

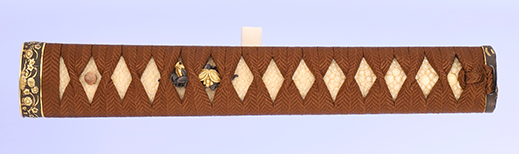

Hilt and scabbard, Shinya Yamada, President's Award 1, Mounting Division, 2020-21

|

Japanese swords may seem to exist in an esoteric world of their own, but with a little background knowledge, appreciation of the beauty of these hand-crafted works of art can be deepened significantly. A new exhibition at the Japanese Sword Museum in Ryogoku, Tokyo, provides such an opportunity to learn more about this traditional artform. On display until 20 September, Contemporary Swords and Artworks introduces Japanese swords made in the last few years alongside some historical examples, allowing visitors to make connections across the centuries.

Before heading to the exhibition on the museum's third floor, it is worth spending a few minutes in the smaller room near the entrance on the first floor. Here the visitor will be introduced to the materials and processes involved in swordmaking and some pointers on what to take into consideration when looking at the exhibits.

The basic process is to melt steel and fold it several times to get rid of impurities and to achieve the desired consistency. The aim is to strike a balance between the hard outside layer that provides the strength of the cutting action, and a softer inner core that cushions the blow. If the core makes the sword as a whole too soft, its cutting strength will be lessened, but if the outer layer is too hard, the blade will be brittle, and may easily break on impact. Reaching the optimum quality takes years of painstaking practice. Later in the production stage, as the blade is forged into shape, the swordsmith pays attention to the quality of the steel finish, the jigane -- what could be likened to the grain, or perhaps the patina, if one were talking about wood. Even if a blade looks as though it has a smooth finish, rarely if ever will it be texture-free. This is one of the most difficult elements of sword appreciation to acquire, and involves looking closely for the subtle patterns the flecks of material make in the steel.

|

|

|

|

|

|

Left: Handguard, Moon Flower and White Plum, Jun Sakai, Achievement Award 2, Fitting Division, 2020. Right: Handguard, Harvest Scene, Seiji Yanagawa, Achievement Award 1, Fitting Division, 2020-21

|

Another detail that is crucial to look for is the hamon, or temper line, which is usually much easier to spot than the jigane. The swordsmith adds a paste of clay along the bottom of the cutting side of the blade, which, once heated and quenched in water or oil, forms a pattern on the blade -- sometimes intricate, sometimes relatively simple. Besides being one of the distinguishing design features of a sword, this hamon has the practical function of hardening the edge.

Once the firing process is complete, the blade is passed over to a professional polisher who will both sharpen it and bring out its innate qualities of shape and texture, and from there the final fittings and scabbard are added to make the finished product. In all, it is a complicated, many-layered process, involving a number of specialized artisans working in unison to achieve a shared goal.

Tachi blade, Tetsushi Kitagawa, Takamatsunomiya Memorial Award, Blade Forging Division, 2021

|

The contributions of these different artisans are recognized in annual swordmaking competitions, and Contemporary Swords and Artworks highlights various swords that have won recognition in these competitions in recent years. The first sword introduced here boasts a hamon that looks soft and even cloudy, and was made this year by Tetsushi Kitagawa, earning him the Takamatsunomiya Memorial Award. As in sumo or kabuki or other arts, swordmakers have a professional name, and it is with this name that they sign their blades. Therefore, Kitagawa's blade is signed Saku Masatada.

These competitions both reflect and reinforce the somewhat formalized world of professional swordmaking. To gain ultimate recognition, an aspiring swordsmith has to win awards in no less than ten competitions. Once this feat is achieved, he or she is granted the title of master and no longer takes part in these competitions, leaving the field open to the next generation of aspiring craftspeople. This is Kitagawa's third consecutive year to win an award, so he is considered on his way to becoming a master as long as he keeps up the quality.

|

|

Tachi blade, Mitsuhiro Kimura, Kunzan Award, Blade Forging Division, 2021

|

Returning to the topic of the temper line, a glance at another prizewinning blade highlights how much variety there is just in this one aspect of the craft. The hamon on a blade by Mitsuhiro Kimura that won the Kunzan Award could perhaps be said to be wilder and more stylized than the Kitagawa blade we saw earlier. Another point of comparison to look out for is the type of sword. Both of these blades are the long tachi type that samurai would use to cut down enemies on the ground when riding on horseback. On the other hand a blade like this one by Hiroshi Yamashita is a shorter sword, known as a tanto:

Tanto blade, Hiroshi Yamashita, Kunzan Award, Blade Forging Division, 2021

|

Contemporary Swords and Artworks also includes historical examples that offer glimpses -- if you look hard enough -- of connections in style and tradition between swords across the centuries. For example, although Kitagawa, the maker of the first sword on display, is from Shiga Prefecture, he works in the Bizen tradition, centered farther west in Okayama -- historically one of Japan's most prolific sword-producing regions. An example of the Bizen style is an unsigned katana (a type of sword as long as a tachi but with a less curved blade) from between 650 and 700 years ago, which won Satoshi Inoue the Kiya Award for his polishing skills. Viewers may be familiar with Bizen through its famous pottery tradition, which, like swordsmithing, utilizes the unique qualities of the region's clay.

Katana, approx. 650-700 years old, polished by Satoshi Inoue, Kiya Award, Sword Polishing Division, 2020-21

|

Another regional connection of note can be spotted when looking at the Kiyohiro blade forged by Toshifumi Morikuni, which won him the Presidents Award this year. It has a simple, understated hamon and is created in the Kyoto style, which makes sense as it shares the subdued elegance of much of the ancient capital's artistic output. An earlier example of this style from roughly 750 years ago earned Takamori Hirai the Excellence Award 3 in polishing, and has a similar subdued, refined quality.

Tachi blade, Toshifumi Morikuni, Presidents Award, Blade Forging Division, 2021 |

Viewers may also notice that the swords on display that have been entered into these competitions are literally just the blades, without any fittings. Elsewhere in the room, however, much attention is paid to the various other components that are an essential part of the final product -- including the hilt, the handguard, and the scabbard. One example that stands out is a set of two hilts made by Takashi Iyama in the traditional way. This involves making an inner core from Japanese whitebark magnolia wood, covering it in white sharkskin, and then binding it tightly in thread in a diamond-shaped design, which not only looks stylish but helps provide a strong grip. For both hilts, Iyama incorporates the only parts that remain from an original Edo-era hilt -- the decorative metal caps at either end of the hilt (the kashira and fuchi) and the menuki decorations under the threads. Each finished hilt brings together old and new in one splendid piece, and ensures the continuance of traditional techniques into the future -- a mission that, more widely, Contemporary Swords and Artworks aims to encourage.

|

|

|

|

Set of two hilts, large (above) and small (below), Takashi Iyama, President's Award 1, Hilt Division, 2020-21 |

All images courtesy of the Japanese Sword Museum. |

|

|

J.M. Hammond

J.M. Hammond researches modernity in Japanese art, photography and cinema, and teaches in Tokyo, including as a faculty lecturer in the English department at Meiji Gakuin University and at Gakushuin University. He has written about art for The Japan Times for over a decade. His essays include "A Sensitivity to Things: Mono No Aware in Late Spring and Equinox Flower" in Ozu International: Essays on the Global Influences of a Japanese Auteur (Bloomsbury, 2015) and "The Collapse of Memory: Tracing Reflexivity in the Work of Daido Moriyama" for The Reflexive Photographer (Museums Etc, 2013) [reprinted in the same publisher's 10 Must Reads: Contemporary Photography (2016)]. He has given various conference papers, including at the University of Hong Kong and the University of Oxford. |

|

|

|