|

Focus features two in-depth reviews each month of fine art, architecture, and design exhibitions at art museums, galleries, and alternative spaces around Japan. |

|

|

|

|

|

Mingei Revisited: Looking at Japan's Folk Art Movement Nearly a Century On

Jennifer Pastore |

|

Dish with green and black glazes (produced by Shoya Yoshida), Ushinoto (Tottori Prefecture), 1930s, The Japan Folk Crafts Museum |

The common objects that fill our lives may be easy to take for granted, but as shown in 100 Years of Mingei: The Folk Crafts Movement at The National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo (MOMAT), with time they may also take on cultural importance -- if not for ourselves, then for society at large. Mingei is short for minshuteki kogei ("crafts of the people"). Takashi Sugiyama, Chief Curator at The Japan Folk Crafts Museum in Tokyo, defines Mingei as "daily products for common people made by unknown craftspeople" (Mingei: Japan's Enduring Folk Arts by Amaury Saint-Gilles). Muneyoshi (Soetsu) Yanagi, Shoji Hamada, and Kanjiro Kawai, three founders of the Mingei movement, coined the term in December 1925. As Mingei comes up on its centennial, this enduring effort to identify and preserve Japan's long tradition of handicrafts warrants reflection. Unlike other shows in recent years, 100 Years of Mingei focuses on the movement's practical rather than philosophical aspects, delving into its historical background and its network of interpersonal connections. Some 450 items are displayed, including pieces collected by Yanagi and other members. The group's publications, personal effects, and archival materials are also featured.

|

|

|

|

|

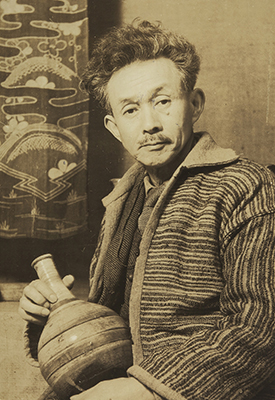

Mingei exponent Muneyoshi (Soetsu) Yanagi in a homespun jacket at The Japan Folk Crafts Museum, February 1948. Photo courtesy of The Japan Folk Crafts Museum

|

To Mingei advocates, modernization was both a threat and a tool. While industrialization and internationalization from the late 1800s coincided with a decline in handicraft practices across Japan, the Mingei movement seized on modern means of production, promotion, and distribution to protect and advance these homespun arts. In April 1939, the first issue of Gekkan Mingei (Folk Crafts Monthly) ran an illustration of the "Tree of Mingei." A museum (The Japan Folk Crafts Museum), a store (Folk Crafts Shop Takumi), and a publishing arm (The Japan Folk Craft Association) made up the three main "branches." (All remain active; Takumi is still in operation in Tottori Prefecture and Ginza, Tokyo, and MOMAT ran a short pop-up shop selling its wares.)

Mingei was not simply about collecting beautiful objects. The movement also developed networks for creating and selling newly made crafts, addressed social issues such as how to improve life in farming regions, proposed ways of reinventing crafts for modern lifestyles, and worked to preserve natural landscapes such as the Tottori Sand Dunes. 100 Years of Mingei details all of these endeavors.

|

|

Faceted jar, with autumn plants design, underglaze blue (bottom part of gourd-shaped jar), Korean Peninsula, Joseon period, early 18th century, The Japan Folk Crafts Museum |

Ceramics are a cornerstone of the Mingei collection. While the movement would become increasingly Japan-centric in the prewar and World War II years, the influence of foreign craft traditions cannot be ignored and is openly discussed in this exhibition, especially in the case of pottery. Yanagi's love of ceramics was sparked by an encounter with a Korean underglazed jar from the 18th century (shown above). Bernard Leach, a British ceramicist who lived in Japan and played an active role in Mingei, introduced English slipware, which movement members also collected during trips to England. (The group also became enamored with English wooden armchairs while abroad.)

In the 1920s and 1930s, a boom in excavating kiln sites across Japan bolstered the popularity of regional ceramics such as the Mino ware of Gifu Prefecture. Ushinoto ware from Tottori (shown at top) and Tanba ware from Hyogo were also actively acquired and produced by Mingei participants.

|

Mokujiki Gogyo, Jizo Bosatsu Statue (Mokujiki-butsu), 1801, The Japan Folk Crafts Museum

|

|

Cotton garment with applique pattern (kiribuse), Ainu in Hokkaido, 19th century, The Japan Folk Crafts Museum (on display for the first half of the exhibition period) |

Yanagi's discovery of a Mokujiki-butsu Buddha statue in Yamanashi Prefecture set him out on a nationwide quest, in 1924, to research these smiling figures carved by the itinerate monk Mokujiki Gogyo (1718-1810). Otsu-e souvenir paintings from Otsu in Shiga Prefecture were another particular interest of Yanagi's. He would mount the pictures on hand-woven Tanba cloth in attractive combinations that reflected the colors and designs of each object. Several examples of Mokujiki-butsu and Otsu-e are exhibited, along with photographs from Yanagi's expeditions.

A wall-spanning, multicolored map of Japan is a highlight of the show. Titled Map of Mingei in Japan (Contemporary Japanese Mingei), it was created for the 1941 exhibition Contemporary Japanese Folkcrafts by the textile designer Keisuke Serizawa to illustrate the findings of Mingei surveys around the country. Indicating which crafts came from where, it conspicuously leaves out Hokkaido, the Japanese settlement of which did not begin in earnest until 1869. Yanagi believed Hokkaido was too "new" to have developed craft traditions worthy of Mingei's attention. For this exhibition, actual items corresponding to the depicted regions are displayed in front of the map.

|

|

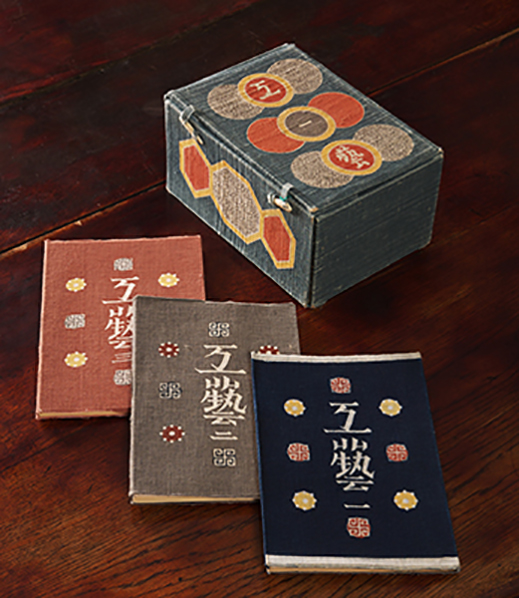

Kogei magazines (nos. 1-3) with storage box, stencil dyed and designed by Keisuke Serizawa, 1931. Photo courtesy of The Japan Folk Crafts Museum

|

The Mingei movement did collect the handicrafts of Hokkaido's indigenous Ainu people. In fact, The Japan Folk Crafts Museum held an exhibition about Ainu craft culture in 1941, and Ainu garments and tools are also presented in 100 Years of Mingei. The section "Local/National/International" explores Mingei activity in the 1930s and 1940s, when East Asia and the "outer" regions of Japan came into focus. Pottery, textiles, tools, and furniture from Korea, China, Taiwan, Hokkaido, Okinawa, and mainland Japan's northern Tohoku region are featured, along with documentation of Mingei initiatives in these areas.

In the postwar era, the Mingei movement followed suit with Japan's reentry into international society and made forays into industrial design. Members resumed travel to North America and Europe. Drawing on similarities between the Mingei ethos and Scandinavian design, an exhibition of Japanese crafts was held in Sweden in 1957, followed the next year by a show about Finnish and Danish design at Tokyo's Shirokiya department store. As Mingei evolved to embrace machine-powered design rooted in craftsmanship, Yanagi's son Sori became a prominent industrial designer known for his furniture and home goods. Sori's ceramic wares, as well as metal smoking pipes designed by Kanjiro Kawai, appear in this exhibition as examples of Mingei innovations of the 1950s and 1960s.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Kyoto Gojozaka Kiln (Kyoto Prefecture), Black teapot (designed by Sori Yanagi), 1958, Yanagi Design Institute (on loan to Kanazawa College of Art)

|

|

Katsuzo Kaneda, Kiseru (traditional Japanese pipes) (designed by Kanjiro Kawai), Shimane Prefecture, 1950s-1960s, Kawai Kanjiro's House |

The Mingei movement is not without its contradictions and controversies. As MOMAT curators Hisaho Hanai and Katsuo Suzuki write, Yanagi in particular showed a lack of awareness that "Mingei itself was a modern product and that the Mingei movement itself would become history." By attempting to place Mingei within its historical context, 100 Years of Mingei takes a vital first step toward addressing this oversight.

All photographs provided by the 100 Years of Mingei: The Folk Crafts Movement exhibition.

|

|

|

Jennifer Pastore

Jennifer Pastore is a Tokyo-based art fan and translator. In addition to Artscape Japan, her words have appeared in ArtAsia Pacific, Sotheby's, and other publications. She is an editor at Tokyo Art Beat.

|

|

|

|