|

Focus features two in-depth reviews each month of fine art, architecture, and design exhibitions at art museums, galleries, and alternative spaces around Japan. |

|

|

|

|

|

Taking the Woodblock Print into the 20th Century: Hasui Kawase

J.M. Hammond |

|

Komagata Embankment, from the series Twelve Views of Tokyo, 1919

|

Vibrant autumn foliage, atmospheric winter snowscapes -- the scenic views from around Japan by Hasui Kawase encompass it all. Although the images he bequeathed to us are serene and peaceful, it was no smooth road to success for the artist.

The current exhibition at the Sompo Museum of Art in Tokyo takes us on a walk along the rocky paths of Hasui's career. Kawase Hasui: Travel and Nostalgic Landscape gathers together close to 300 of his works, all of which are woodblock prints (hanga). Hasui (1883-1957) was born Bunjiro Kawase in Tokyo. Although his parents expected him to take over the family's braid business, he instead pursued his goal of making a career in art. In his twenties he asked to be apprenticed to the respected Nihonga artist Kiyokata Kaburaki, but the master turned Hasui down, advising him to spend some time studying Western art. This he did, coming back to Kiyokata a few years later, and, being accepted this time, threw himself into his studies. He was drawn in particular to the art of woodblock prints, and began working with the print publisher Shozaburo Watanabe, the driving force behind the shin-hanga (new prints) movement. This new direction in printmaking aimed to revive the art form, which had lost ground in modern, internationalizing Japan, by incorporating aspects of Western art such as a heightened sense of realism, light and shade to bring out form, and linear perspective.

|

|

|

|

|

Okane Road, Shiobara, 1918

|

Hasui's early prints, in comparison with his later works, appear somewhat rough in texture. This largely derives from his use of the zara-zuri technique of scraping marks onto the woodblocks. This style was uncommon in traditional prints, such as ukiyo-e, but became a signature feature of many "Watanabe prints" -- images produced by the various artists working with the publisher. It can be seen in Okane Road from 1918, one of three prints Hasui made of views in Shiobara, Tochigi Prefecture. The favorable response to this series spurred Hasui to adopt the life of a traveling artist, making sketches in the places he visited and working them into prints after returning to Tokyo.

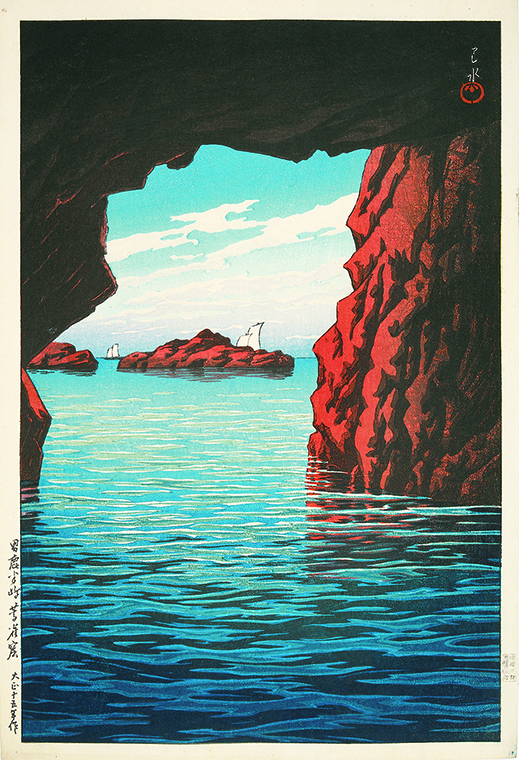

The Great Kanto Earthquake of 1923 severely disrupted Hasui's activities, as the subsequent fires engulfed his house, consuming his entire collection of sketches. It was a huge blow, but Watanabe urged Hasui not to be despondent and pushed him to travel, and create, once more. Souvenirs of Travel, Third Series, produced between 1924 and 1929, saw the consolidation of Hasui's personal style -- clear and sharp, and, at the behest of his publisher, increasingly vivid in color, as seen in the deep crimson and brilliant blue of Kojaku Cavern, Oga Peninsula from 1926.

|

|

|

|

|

Kojaku Cavern, Oga Peninsula, from the series Souvenirs of Travel III, 1926

|

During the same period, Hasui was working on his Twenty Views of Tokyo series, from which come a number of his most celebrated images, among them Zojo-ji Temple, Shiba, depicting a woman in kimono braving the elements. By now, Hasui was establishing some of the motifs he would return to throughout his career. For example, when he portrayed temples or shrines, they were invariably shrouded in snow.

Whatever the season or time of day, a sense of quiet and calm prevails. Hasui's compositions tend to be devoid of people, or any figures that appear are just one element of the scene. Usually, their faces are turned away or they are deep in the picture, leaving their expressions concealed and allowing the viewer to imagine what they might be feeling.

|

Zojo-ji Temple, Shiba, from the series Twenty Views of Tokyo, 1925

|

|

Moon at Magome, from the series Twenty Views of Tokyo, 1930 |

Hasui's work was lauded in Japan and also overseas, but this came hand in hand with criticism that his images were becoming stereotypical, as well as stylistically derivative of the ukiyo-e legend Utagawa Hiroshige. During the 1930s, feeling his work had fallen into cliche, Hasui suffered a creative slump. One can, to an extent, see why. The range in style is too narrow, the recurring views and motifs too familiar -- not to mention that at times he skates too close to twee with, for example, the occasional addition of a colorful rainbow, as in Hatta, Kaga Province.

Hatta, Kaga Province, from the series Souvenirs of Travel III, 1924

|

Nonetheless, it is also difficult to find another artist who can actually make tangible the crisp, refreshing feel of breathing in the air of a clear winter day -- but that is what Hasui achieves in Mt. Fuji and Oshino Village in Clear Weather after Snow.

Mt. Fuji and Oshino Village in Clear Weather after Snow , 1952

|

Two events in particular helped Hasui get back on track, one of these being a trip to Korea, which rejuvenated his creative spirit. He revisited the kind of grand-scale compositions that he had worked on in his early years, producing, among other works, Nakhwa Rock, Puyo -- a magnificent view of a huge cliff face with a sailboat gliding by in the foreground.

November: Lake Towada, Calendar for Pacific Transport Lines, 1953 |

The other catalyst for Hasui's recovery was a boom in the market for prints in the wake of the Second World War, particularly with demand from the Allied Occupation forces then in Japan. At times, his coloring is more dynamic than ever, as in the scene of autumn leaves in November: Lake Towada from 1953. In images published that same year in a calendar for Pacific Transport Lines, he is also more inventive in his compositions than usual: his view of Enoshima is framed by the partition and wooden veranda of what is likely an inn at this resort.

August: Enoshima, Calendar for Pacific Transport Lines, 1953 |

Towards the end of his life, Hasui received some official recognition. In 1952, Japan's Ministry of Education commissioned him to make some prints to be kept permanently as part of its cultural property preservation initiative, and he came forward with another take on Zojo-ji temple in the snow. The two female figures in the scene are said to be his wife and daughter. Just four years later Hasui died, leaving behind a vast array of refined, tranquil images.

Snow at Zojo-ji Temple, 1953 |

All images are woodblock prints by Hasui Kawase, courtesy of S. Watanabe Woodcut Prints.

|

|

|

J.M. Hammond

J.M. Hammond researches modernity in Japanese art, photography and cinema, and teaches in Tokyo, including as a faculty lecturer in the English department at Meiji Gakuin University and at Gakushuin University. He has written about art for The Japan Times for over a decade. His essays include "A Sensitivity to Things: Mono No Aware in Late Spring and Equinox Flower" in Ozu International: Essays on the Global Influences of a Japanese Auteur (Bloomsbury, 2015) and "The Collapse of Memory: Tracing Reflexivity in the Work of Daido Moriyama" for The Reflexive Photographer (Museums Etc, 2013) [reprinted in the same publisher's 10 Must Reads: Contemporary Photography (2016)]. He has given various conference papers, including at the University of Hong Kong and the University of Oxford. |

|

|

|