|

Focus features two in-depth reviews each month of fine art, architecture, and design exhibitions at art museums, galleries, and alternative spaces around Japan. |

|

|

|

|

|

Inspiration from Foreign Shores: The Impact of Japan on the Art of Joan Miró

J.M. Hammond |

|

Gallery view, Joan Miró and Japan exhibition, with Untitled (Homage to Takiguchi Shuzo), the three works at center (1970). Photo by Yuya Furukawa |

The impact of Japanese art and culture on European artistic circles is wide and varied, yet its full scope remains largely unknown, even to many keen art enthusiasts. The Spanish artist Joan Miró (1893-1983) is a case in point. While his images are familiar to many in Japan and abroad, the Japanese influence on his work is a less familiar topic. A new exhibition at The Bunkamura Museum of Art in Tokyo aims to document the connections and interactions between Miró and Japanese artists and cultural figures, and to bring into focus how his interest in Japanese culture may have affected his creative process. Joan Miró and Japan assembles about 140 exhibits, ranging from Miró's own artworks to Japanese prints, pottery and more.

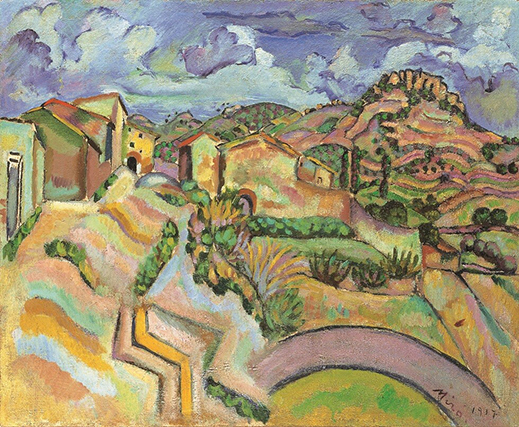

In his early works, however, Miró's most evident artistic interests are the various trends in European painting of the day, as seen in two oil paintings of the village of Siurana that give a nod to the structural muscle of Paul Cézanne's work.

|

|

Siurana (1917), Yoshino Gypsum Collection (deposited at Yamagata Museum of Art) |

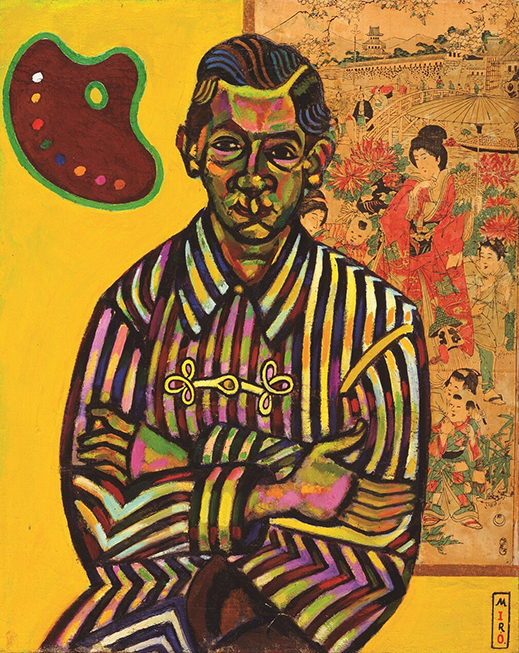

In his 1917 Portrait of Enric Cristòfol Ricart, Miró depicts his friend in colors chosen for their expressive qualities rather than any claims to naturalism, in a manner that recalls the techniques of the Fauvist painters of his day.

|

|

|

|

|

Portrait of Enric Cristòfol Ricart (1917) © The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Florene May Schoenborn Bequest, 1996 / Licensed by Art Resource, NY

|

At the same time, Miró portrays Ricart with a Japanese print on the wall behind him. It is evident that while Miró faithfully replicated the composition of the original print (also exhibited here), he deliberately transformed the bright reds into paler hues for his work. Presumably this was done so as not to clash with or distract from the figure of his friend.

The print is likely one from Ricart's own collection. As well as being a keen ukiyo-e enthusiast, he was a translator of Japanese haiku poetry, and was responsible in no minor way for introducing Miró to certain aspects of Japanese culture.

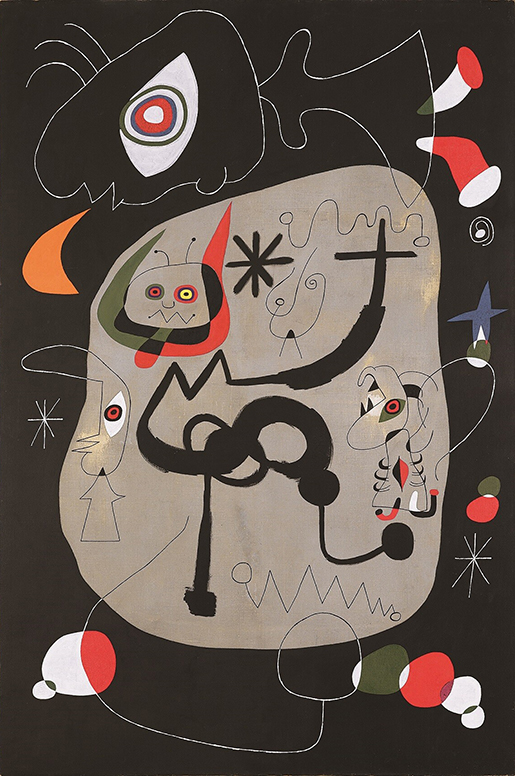

It is Surrealism, however, that Miró was most closely associated with throughout his career, even as he said he preferred not to be categorized by any "isms." One section of the exhibition introduces about a dozen works from the 1920s and 30s, when he spent a lot of time in Paris and was working closely with key figures of the Surrealist movement. Composition with Figures in the Burnt Forest from 1931 shows Surrealist tendencies as well as Miró's trademark playfulness, with some elemental forms of circles and triangles -- and a motif that recurs frequently in his imagery, the human eye.

|

|

Composition with Figures in the Burnt Forest (1931) © Fundació Joan Miró, Barcelona |

Miró was a peripheral member of the ADLAN art group, which organized his first exhibition, as well as others featuring Japanese ceramics and folkcrafts from the collections of two Catalans who had lived in Japan, the traveler Cels Gomis and the sculptor Eudald Serra. Miró was delighted by the kokeshi dolls, koinobori carp banners, and other artifacts he saw on display, some of which are included in Joan Miró and Japan.

|

|

|

|

|

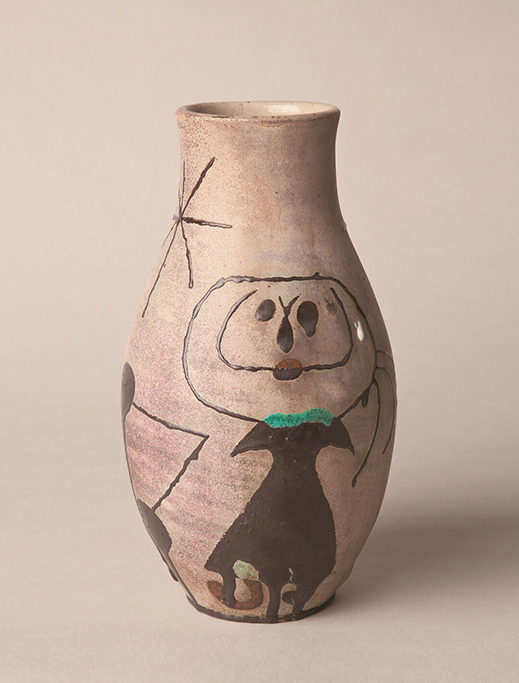

Josep Llorens i Artigas and Joan Miró, Vase (1946)

|

Also to be seen here are the books that Miró began collecting on Japanese art and aspects of the country's culture, such as Zen, calligraphy, and the tea ceremony. Miró also became increasingly knowledgeable about Japanese art through working with his potter friend Josep Llorens i Artigas, who had studied various Japanese kiln techniques. While they started their collaboration with Artigas throwing the clay and Miró decorating the resulting vessels, over time they began to work more closely together.

Exhibitions of Miró's prints and other works had been held in Japan since 1962, and the first major show here featuring his paintings took place in 1966. This served as the occasion for the artist's first trip to the country, which saw him stay for two weeks. Miró was actively involved in the planning of the event, creating a lithograph to be used in the exhibition poster.

Photographs taken during the trip include one of him at Ryoanji in Kyoto, gazing at the temple's rock garden. In Japan Miró would meet, for the first time, such cultural figures as ikebana master Sofu Teshigahara, and catch up with Taro Okamoto, with whom he was at least familiar from the Japanese artist's involvement in Parisian avant-garde circles in the 1930s.

Highlighting just how quickly those in the know in Japan became aware of cutting-edge developments in European art, it is noteworthy that the first monograph on Miró anywhere in the world was actually published in Japan -- and as early as 1940. On this visit, Miró had the opportunity to finally meet the author of that work, Shuzo Takiguchi, a poet and long-standing champion of the Surrealist movement.

|

|

Makimono (1956), Machida City Museum of Graphic Arts |

The question remains, however, as to precisely how Japan influenced Miró. The answer is far from straightforward, as there is little in his oeuvre that is overtly and unambiguously inspired by Japanese art. One rare indication of a clear and direct influence might be found in his choice of format -- for example, the long hand-scroll format of a number of works on display here, such as Makimono, although this was made in 1956 before he came to Japan.

|

|

|

|

|

Dancer Hearing an Organ Playing in a Gothic Cathedral (1945), Fukuoka Art Museum

|

|

|

|

|

|

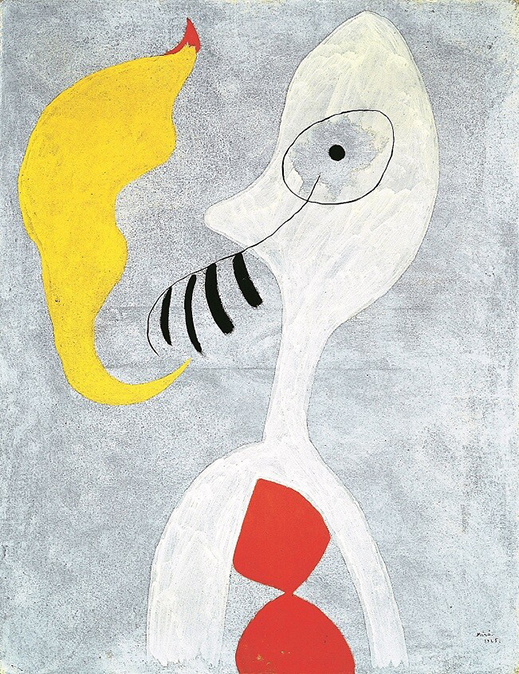

Painting (Head of a Smoker) (1925), Toyama Prefectural Museum of Art and Design

|

Miró's penchant for including words in some of his works -- creations that he called painting-poems -- has a notable similarity to traditional Asian ink paintings that often contain poems or inscriptions. Whether this is a direct influence from Japan or merely a coincidence is unclear, but Miró himself did at one point comment on this correspondence.

The influence of Japan on Miró's art can, however, be sensed in his relationship with materials. We can see Miró enjoying the way his gouache and india ink is absorbed into the paper in the three works known as Untitled (Homage to Takiguchi Shuzo) from 1970, much as it occurs in Asian ink painting and Japanese calligraphy. While this work was made after his two trips to Japan, his curiosity was already aroused as early as the 1940s, when the artist was working with sumi ink and wrote in his memos about Japanese paper and brushes.

Indeed, while the motifs and figures in many of Miró's most representative works are typically rendered with thin, scrawling lines, his brushstrokes become thicker, bolder and stronger in some works through the 1970s. Whether this is the direct result of seeing more Japanese calligraphy up close during his time in Japan, including his second trip in 1969, is, however, unclear.

The works that we could say at least show a close affinity with a Japanese sensibility would be the handful of large-scale, stark monochrome paintings that close the exhibition. With wide swathes of black and white paint, Miró comes close to the Zen state of mind reflected in much Japanese ink painting -- or, a little closer to home, to the vast emptiness associated with Mark Rothko's canvases.

All in all, Joan Miró and Japan may be somewhat inconclusive concerning the exact nature of Japan's impact on Miro's art, but the exhibition lays out a comprehensive case for considering the significance of cross-cultural influences in the world of artistic creativity.

|

|

Gallery view, Joan Miró and Japan exhibition. Photo by Yuya Furukawa |

All works shown are by Joan Miró except where otherwise noted; © Successió Miró / ADAGP, Paris & JASPAR, Tokyo, 2022. Images are courtesy of The Bunkamura Museum of Art. |

|

|

J.M. Hammond

J.M. Hammond researches modernity in Japanese art, photography and cinema, and teaches in Tokyo, including as a faculty lecturer in the English department at Meiji Gakuin University and at Gakushuin University. He has written about art for The Japan Times for over a decade. His essays include "A Sensitivity to Things: Mono No Aware in Late Spring and Equinox Flower" in Ozu International: Essays on the Global Influences of a Japanese Auteur (Bloomsbury, 2015) and "The Collapse of Memory: Tracing Reflexivity in the Work of Daido Moriyama" for The Reflexive Photographer (Museums Etc, 2013) [reprinted in the same publisher's 10 Must Reads: Contemporary Photography (2016)]. He has given various conference papers, including at the University of Hong Kong and the University of Oxford. |

|

|

|