|

|

|

HOME > FOCUS > An Eye for Line, a Flair for Color: The Design Works of Seifu Tsuda |

|

|

Focus features two in-depth reviews each month of fine art, architecture, and design exhibitions at art museums, galleries, and alternative spaces around Japan. |

|

|

|

|

|

An Eye for Line, a Flair for Color: The Design Works of Seifu Tsuda

J.M. Hammond |

|

Seifu Tsuda, from Uzuragoromo, published by Yamada Unsodo, 1903, collection of Scott Johnson. Image © Rieko Takahashi |

During the Meiji (1868-1912) and Taisho (1912-1926) eras, artists in Japan met with new challenges and opportunities as the country opened up more to the West, but they also had to make certain tough decisions on where to focus their energy.

Artists responded in a variety of ways -- choosing either to continue with the Japanese styles they were familiar with, or adopting the imported Western oil painting tradition, or attempting a conscious synthesis of both. Some felt they needed to side with either "art" or with "design" -- a distinction that had never been clear or important in Japan. The approach of Seifu Tsuda (1880-1978) was to simply do whatever he was interested in, regardless of labeling and categorization.

To the extent that Tsuda is known in Japan today, it is largely for his proletarian art, critical of the political status quo, which landed him in prison for a brief spell in the 1930s. Now, an exhibition at the Shoto Museum of Art in Tokyo focuses on Tsuda's career up to that point, particularly his work in the field of design. Tsuda Seifu -- the designs, the time and… explores how Tsuda sought out and incorporated a range of ideas, techniques and styles into his designs, presenting close to 200 works by him, his contemporaries and associates, as well as relevant items from Japan and overseas that highlight the cultural climate of the time.

|

|

Seifu Tsuda, from Senshoku zuan, published by Yamada Unsodo, 1904, collection of Unsodo. Image © Rieko Takahashi |

Tsuda was born into a Kyoto family that ran an ikebana flower-arrangement school. But the family's fortunes had suffered as a result of changes brought about by modernization and the Meiji Restoration -- including the relocation of the capital from Kyoto to Tokyo -- and they began to operate as a florist as well, selling flowers from their home. The family business was taken over by Tsuda's elder brother, Issotei Nishikawa, leaving Seifu free to pursue his interest in art and culture.

Much of Tsuda's output in the first decade of his career consisted of zuan -- designs, often collected in albums called zuanshu, that were not created for a specific purpose, but rather as reference material for use in various creative industries. In practice, one of the main uses of these pattern books was in the production of kimono. In fact, Tsuda's primary employer at this time was a weaving company that made textiles for kimono -- but mainly those for Buddhist priests, and therefore of somber coloring and design.

Traditionally, zuan had been produced by anonymous artisans, but by the Meiji era it was becoming common for established artists to design them. Tsuda had been inspired to try his hand after seeing prints by the slightly older artist Sekka Kamisaka, who was, arguably, the last major figure to be closely associated with the centuries-long Rinpa painting tradition.

|

|

|

|

|

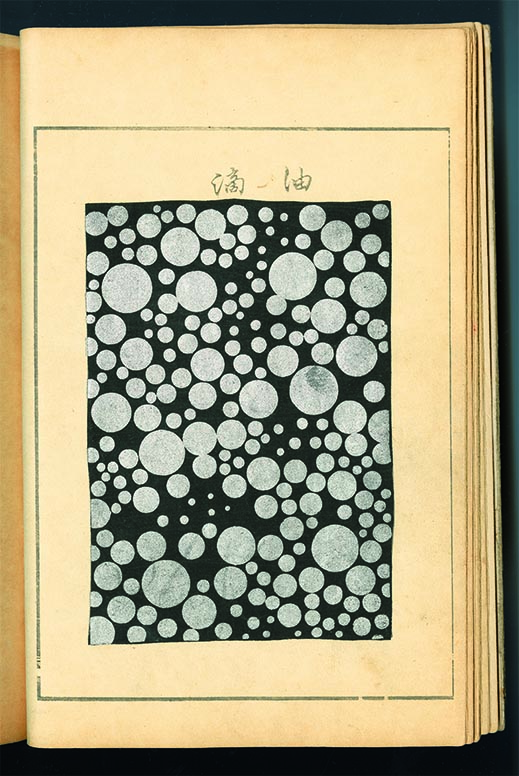

Seifu Tsuda, Oil Drops, from Kamon-fu, published by Honda Unkindo, June 1899, collection of Unsodo. Image © Rieko Takahashi

|

In 1896 Tsuda, then 16, took a selection of his pattern designs (not included in this exhibition, and it is unknown if they still exist) to a Kyoto bookseller and publisher who gave him money on the spot and promised to publish them, as well as more of his designs in the future.

The exhibition opens with a different collection of zuan, designs Tsuda made with kimono in mind around the turn of the century. Frequently, these incorporate motifs from nature such as flowers and birds, but they can also verge on the abstract, as seen in a striking pattern of silver dots on a dark blue background, inspired by oil spots. This eye for natural motifs put Tsuda in good stead when new art styles arrived from Europe, such as Art Nouveau, that incorporated not only similar motifs from nature, but also an undeniable Japanese influence. For Japanese artists like Tsuda, Art Nouveau in many ways represented a familiar visual sensibility repackaged for the age. Certain of his works, such as Uzuragoromo, reflect his interest in this new style.

|

|

Seifu Tsuda, from Uzuragoromo, published by Yamada Unsodo, 1903, collection of Scott Johnson. Image © Rieko Takahashi |

Tsuda's prolific production of zuan was limited to the first decade of his career. In 1905 he left the comfort of Kyoto to work as a medic in the Russo-Japanese War. It seems Tsuda was something of a restless soul, studying Japanese art for some time, then Western-style art under Chu Asai, even traveling to Paris to study at the well-regarded Academie Julian. He carried on painting throughout his life, later shifting his focus from Western- to Japanese-style art. With the exhibition's emphasis on his designs, however, there are only a few paintings on display to show us that side of his output.

Seifu Tsuda, Zuan from the Battlefield, no. 2, from Shobijutsu zufu, published by Yamada Unsodo, 1904, collection of Unsodo. Image © Rieko Takahashi |

On his return from Paris in 1910, Tsuda based himself in Tokyo. Much of his design work now revolved around making book covers -- most notably for works by the renowned author Soseki Natsume, such as Grass on the Wayside. At least a dozen of these designs spanning a number of years are collected here; they show a subdued, refined sense that somehow seems in keeping with Soseki's world.

Grass on the Wayside, designed by Seifu Tsuda, written by Soseki Natsume, 1919 (13th printing, first edition 1915), collection of Yamada Toshiyuki. |

Although much of what Tsuda produced was commissioned as designs for particular products, another aspect of the artist's mission was to make art and design something that could enrich people's day-to-day lived experience. In line with this idea, Tsuda would make various one-off objects and artworks by hand and sell them to interested customers at gallery shows.

Tsuda also formed a loose collective with his elder brother, Issotei, who made zuan, and his friend Koko Asano, who specialized in lacquerware, to design objects for everyday use. Together they launched a small movement dubbed Shobijutsu (Small Art). Sometimes the group would rope in friends such as Chu Asai, who designed dishes like these:

Two works designed by Chu Asai, produced by Koko Sugibayashi: Sweets Dish with Swimming Fishes, maki-e lacquerware, 1909 (left), and Soup Bowl with Cats, lacquerware, date unknown (right); collection of Sakura City Museum of Art. |

|

|

|

|

|

Seifu Tsuda, Wall Hanging with Embroidery, 1913, collection of The National Museum of Modern Art, Kyoto. Image © Rieko Takahashi

|

Tsuda also became active in areas not usually associated with artists, such as embroidery. He was tasked with creating a tablecloth for the home of Eiichi Shibusawa, the influential businessman and driving force behind Japan's modernization. The actual tablecloth is no longer in existence, having graced the table at too many dinners to survive to the present (it is represented here in a photograph of Shibusawa's dining room), although other examples of Tsuda's skill with the needle are on display.

However, it is the zuan by Tsuda, as well as those by associated artists, that are the main focus of Tsuda Seifu -- the designs, the time and… Colorful and stylish, these overlooked designs may well find new appreciation among art lovers today, a century or more after their creation.

|

| Tsuda Seifu -- the designs, the time and… |

| 18 June - 14 August 2022 |

| Shoto Museum of Art |

|

The exhibition is in two parts, from 18 June to 18 July and from 20 July to 14 August; some works will be replaced when the exhibition period changes. Also, advance booking is required for certain days, so please check the museum website.

|

|

|

|

J.M. Hammond

J.M. Hammond has been researching and writing about Japanese art, traditional and modern, in various media for close to two decades. He has had essays on art and cinema printed in various book projects. These include "A Sensitivity to Things: Mono No Aware in Late Spring and Equinox Flower" in Ozu International: Essays on the Global Influences of a Japanese Auteur (Bloomsbury, 2015) and "The Collapse of Memory: Tracing Reflexivity in the Work of Daido Moriyama" for The Reflexive Photographer (Museums Etc, 2013) [reprinted in the same publisher's 10 Must Reads: Contemporary Photography (2016)]. He has given various conference papers, including at the University of Hong Kong and the University of Oxford. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|