|

Focus features two in-depth reviews each month of fine art, architecture, and design exhibitions at art museums, galleries, and alternative spaces around Japan. |

|

|

|

|

|

Farewell to the Nakagin Capsule Tower: A Brief but Exquisite Glimpse into a Metabolist Future

James Lambiasi |

|

A detached capsule being carefully lowered by crane. Photo by Nakagin Capsule Tower Preservation and Restoration Project |

Tokyo is a city of rapid change. Its insatiable appetite for new construction has persisted through economic highs and lows ever since the postwar construction boom, and there is little room for sentiment when a building succumbs to the pressures of its own land value and is replaced. This is the environment that gave birth to the Nakagin Capsule Tower in 1972, a revolutionary micro-apartment building by architect Kisho Kurokawa that became the iconic representation of the Metabolist movement in Japan. It is also, however, the same economic ecosystem that is helping bring about its demise: the demolition of Kurokawa's futuristic masterpiece began on 12 April 2022. As an architect practicing in Tokyo for 27 years, I cannot recall a building demolition in Japan that has attracted such global attention and debate, a testament to Nakagin's great influence and importance.

|

|

|

|

|

Exterior View of the Nakagin Capsule Tower. Photo by Zoe Ward, Japan Property Central

|

Just as Le Corbusier's principle "a house is a machine for living" gained cachet with his 1927 manifesto Toward an Architecture, Kurokawa's radical capsule apartment concept crystallized a new way of living for the Tokyo salaryman during the postwar boom. The Nakagin Capsule Tower's original sales pamphlets in the early 1970s proudly declared that "this capsule will provide a good living space and a secluded environment in which to select and evaluate business data." Perhaps "evaluating business data" is a clever euphemism for a nocturnal roost after nightly drinking binges with fellow salarymen, but in any case the sleeping capsule concept ushered in a new era of Japanese society in which loyalty to the company workplace rose in hierarchical prominence and forever altered traditional Japanese family structure.

The Nakagin Capsule Tower came to embody the 1970s Metabolist movement due to its conceptual clarity as a rational structure of two identical square cores that support premanufactured capsules attached as independent pods. The term "metabolism" describes the biological process of natural growth, and signifies that impermanent aspects of change, adaption, and renewal can actually be utilized to ensure longevity. Just as a tree has a permanent trunk and branches, yet sheds its leaves in the winter, one typology of Metabolist architecture is that a building with a permanent central core can adapt, evolve, and ultimately survive longer if its extremities are interchangeable.

This Metabolist philosophy of designing structures based on natural cycles was in many ways before its time, and we see that such concepts as interchangeability, preassembly, and recycling are still being explored today. It is also profound to note that as much as this movement is viewed as futuristic, it can actually be interpreted as a natural extension of preexisting philosophies imbued in traditional Japanese architecture, which for centuries has utilized impermanence to maintain longevity. For example, the subtle parabolic curve of a temple roof is ideal for distributing the downward forces of kawara roof tiles and thereby minimizing the need for mortar. When an earthquake occurs, the tiles can be shaken off before the weight of the roof brings down the entire structure. Prewar Tokyo was a city of wood and extremely susceptible to fire. Wooden structures therefore required joinery instead of nails so as to ensure that buildings could be torn down to create fire blocks, thus preserving the city as a whole by sacrificing a portion of it.

|

|

Many residents took part in the effort to save Nakagin, as is evident from this window sign. Photo by Zoe Ward, Japan Property Central |

Kurokawa envisioned the interchangeable capsules of Nakagin as being replaced over time, thereby extending the lifespan of its core structure by accommodating new capsules that would adapt to a changing environment. Unfortunately, design flaws prevented this concept from being realized. Since all of the 140 capsules were attached vertically instead of horizontally, it was impossible to replace one capsule without also replacing all of the capsules above it. As earthquake safety standards grew stricter over the years, the building came to be deemed an earthquake hazard, and the spray asbestos that was used extensively in its construction plagued attempts at major renovations. The year 2007 proved pivotal to the ultimate demise of Nakagin; that was when the landowner decided that logistical and financial arguments against maintaining the building were so compelling that redevelopment was necessary. Kisho Kurokawa passed away that same year, meaning the loss of an influential proponent of the building's preservation. As fate would have it, however, the 2008 global economic downturn caused redevelopment plans to be scrapped, thus creating more time to try to resuscitate Nakagin from its decrepit condition.

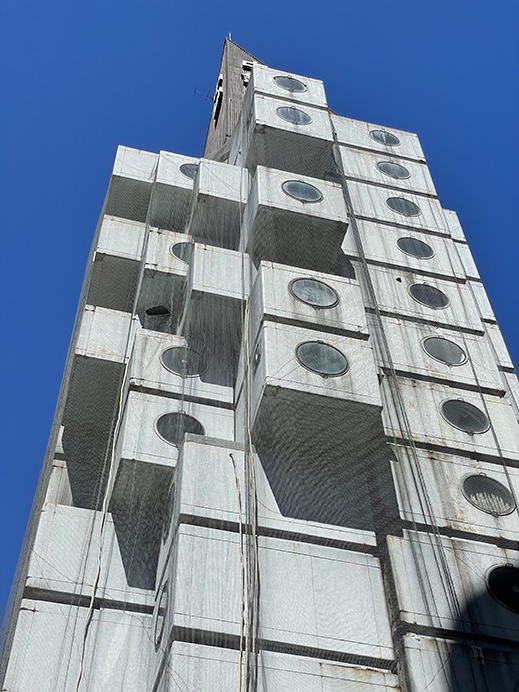

I was able to take a private tour of the Nakagin building in 2014. It was immediately evident that the structure was in serious disrepair, as it was shrouded in a huge net to prevent rust and debris from falling onto pedestrians. A tour of the interior only reinforced my impression that achieving a turnaround of fortune for Nakagin would be a major task. Some residents secured their own water supply by running pipes through holes in their front doors; collapsing ceilings were commonplace; and ingenious networks of interconnected PET bottles allowed residents to drain water from their leaky ceilings to the exterior corridors. With the centralized hot-water supply no longer functioning, residents who wanted a hot shower shared a freestanding shower booth located in the ground-floor custodial court, which was visible from the street.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Nakagin Capsule Tower shrouded in net to catch falling debris. Photo by James Lambiasi

|

|

By May 2022 the scaffolding started to envelop Nakagin in preparation for demolition. Photo by James Lambiasi |

Over the years, even as the number of residents dwindled due to the deteriorating living conditions, valiant efforts were made by the remaining residents and supporters to save Nakagin. The Nakagin Capsule Tower Preservation and Restoration Project fought hard through public petitions and crowdfunding campaigns, tours were conducted to raise the visibility of the effort among visitors, and inclusion in the Docomomo list of endangered buildings created international awareness of its plight.

To learn more about the underlying causes that led to Nakagin's ultimate demolition, I consulted Zoe Ward, CEO of Japan Property Central, a real estate brokerage in central Tokyo that, in addition to publishing reports on real estate-related news, has kept a keen eye on the buildings of historic value that are all too often razed due to their property value. Zoe explained that the movement to preserve the Nakagin building suffered another major blow in 2018, when the site was sold to an LLC (limited liability company). In 2019 there was a glimmer of hope that a foreign company sympathetic to the preservation of Nakagin might step in, but this unfortunately did not happen due to the Covid-19 pandemic. Meanwhile the LLC gradually bought up the capsules, and by November 2020 they had obtained approval from enough of the voting right holders to carry out the demolition of the building. According to Ward, under the current Act on Special Measures Concerning the Reconstruction of Condominiums Destroyed by Disaster, 100 percent of right holders are normally required to vote in favor of demolition and selling off land rights; however, only 80 percent is permissible in cases when the building is damaged or deemed a hazard risk -- thus sealing the fate of Nakagin. In the spring of 2021, the capsule owners' association released the official news confirming their intention to demolish the Nakagin Capsule Tower and return the leasehold land rights to the LLC landowner.

|

|

|

|

|

The Shizuoka Press and Broadcasting Center after its recent refurbishment in 2022. Architect: Kenzo Tange, 1967. Photo by Zoe Ward, Japan Property Central

|

While it is an unfortunate fact that Japan is losing many important examples of Metabolist architecture as property values eventually outweigh the burdens of maintenance, thankfully there are some cases where the cultural value of the Metabolist legacy is recognized and an effort is put into preservation. The Shizuoka Press and Broadcasting Center in Shinbashi, Tokyo, for example, was built in 1967 by Metabolist master architect Kenzo Tange. Similar to (and not far from) the Nakagin Capsule Tower, it, too, boasts a solid central core with cantilevered "pods" attached at random positions, providing a comparative perspective on the types of buildings produced by the Metabolist movement. Open terraces between the pods form the same random composition, visually conveying the philosophy of flexibility in the future. In this case, Tange proposed that the void spaces between pods could be filled in with office space as needed. While this has never come to fruition, it is encouraging that the newly refurbished offices are being advertised online, and according to the planning department of the owner, SBS, there are currently no plans to demolish and replace this iconic building.

Regarding the future of Nakagin, I was able to speak with Tatsuyuki Maeda, founder of the Nakagin Capsule Tower Preservation and Restoration Project. Through years of devotion to Nakagin, Maeda has remained undaunted, as is evident from the group's Instagram page, which diligently documents the dismantling of Nakagin capsule by capsule. According to Maeda, to date there have been over 100 inquiries from museums around the globe that would relish the opportunity to display a capsule at their institution. He explains, however, that it is a laborious process to evaluate each capsule as it is taken off the building, and only after the process is complete can they address all these requests. Of the 140 capsules to be taken from the building, his hope is that 20 or more will be in good enough condition to display in a museum.

I recall the excitement generated when the Mori Art Museum displayed one of the capsules in Roppongi during its Metabolism: The City of the Future exhibition in 2011, and it is encouraging to think that capsules displayed in this way will increase awareness of Japan's exquisite experimentation during the Metabolist era. Like seeds floating off into the air to spawn new life, these capsules putting down new roots around the world could represent the ultimate fulfillment of Kisho Kurokawa's dream of a truly Metabolist architecture.

|

|

|

|

|

|

Exterior and interior photos of a capsule on display during the Mori Art Museum exhibition Metabolism: The City of the Future in 2011. Photos by James Lambiasi |

|

|

James Lambiasi

Following completion of his Master's Degree in Architecture from Harvard University Graduate School of Design in 1995, James Lambiasi has been a practicing architect and educator in Tokyo for over 26 years. He is the principal of his own firm James Lambiasi Architect, has taught as a visiting lecturer at several Tokyo universities, and has lectured extensively on his work. James has served as president of the AIA Japan Chapter in 2008, and frequently appears on the NHK series "Journeys in Japan" as an architectural critic.

|

|

|

|