|

Focus features two in-depth reviews each month of fine art, architecture, and design exhibitions at art museums, galleries, and alternative spaces around Japan. |

|

|

|

|

|

A Tribute to the Spirit of Okinawa: Bashofu at the Okura Museum of Art

Susan Rogers Chikuba |

|

Bashofu textile production begins with cultivation of the ito-basho plant, a variety of wild banana indigenous to the Ryukyus. The stalks are tended for three years until their fibers are ready for harvest. It takes 200 of them to yield enough high-grade fiber for a single kimono. © Atsushi Higa / Photo Studio Tsuha |

The handiwork and artistry of Kijoka weavers were on full display in Tokyo these past two months at the Okura Museum of Art, where a special exhibition on the textile legacy of Toshiko Taira showcased the dyeing and weaving innovations that have made the plantain-fiber cloth known as Kijoka Bashofu sought by the finest kimono shops. Taira was born in Kijoka, a hamlet at the north end of the main island of Okinawa, in 1921. After World War II she founded a weaving cooperative there, and rallied women residents to revive the local textile-making skills that had nearly died out amid the war's devastation. Kijoka Bashofu was designated a national Important Intangible Cultural Property in 1974, two years after U.S. occupation of Okinawa ended. Taira herself was distinguished separately in 2000 as the Holder of that asset for Bashofu, a title popularly known as Living National Treasure.

|

|

|

|

|

Taira works at forming the bashofu yarns, a task she carries out daily. No fewer than 22,000 knots are made to produce enough threads for one bolt of kimono cloth. © Naruyasu Nabeshima © Kateigaho

|

From growing the ito-basho plant, to harvesting its fibers and forming and dyeing the yarns and weaving the ikat cloth, every labor-intensive step in the art of bashofu-making is performed by hand. Even the tools are handmade, often of bamboo. In Kijoka some 30 distinct processes, each involving multiple steps, go into the creation of a single bolt of the textile, and Taira continues to work in her studio daily even now, at the age of 101. Her primary focus these days is u-umi, the delicate task of splitting and joining the fibers to form the yarns. Using a small knife and her fingernails, she splits each length of fiber from the root end into separate threads, which she sorts and matches for weight, texture, and color. She then joins the strands with a weaver's knot, pulled tight and clipped short. As thread uniformity and the evenness of the joins affect the ultimate quality of the cloth, exacting care is needed. Veterans like Taira can produce 20 grams (0.7 ounces) of the precious threads a day.

|

|

Pre-dyed warp threads, or pattern yarns, are the essential component of ikat textiles. They are colored prior to weaving by the precisely measured tying of resists, so that the envisioned patterns later emerge on the loom when woven with solid-color ground yarns. © Atsushi Higa / Photo Studio Tsuha |

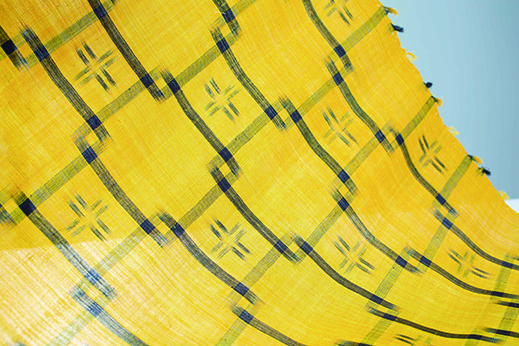

Suspended from the ceilings of the museum's first-floor gallery were brightly colored swathes of the nigashi style of bashofu, in which the yarns are refined by boiling in a wood-lye solution to soften the fibers and heighten their penetrability by dyes. The method dates back to the days of the Ryukyu Kingdom (1429-1879), when brighter hues were sought for the reds and yellows worn by members of the royal court. Taira and her fellow weavers revived the technique and over the years developed a vivid palette of new botanical colors made possible by this extra step in processing.

Birds and shifted woven ikat pattern with stripes on a red ground; Ryukyu indigo, red bayberry, garcinia, and Indian madder dyes; Taira Bashofu Studio, Heisei era (1989-2019). © Atsushi Higa / Photo Studio Tsuha |

Also featured were some of the advanced weaving techniques used in Kijoka: translucent gauze or leno-weave constructions that have a sheer, gossamer quality; the tiny flower-like patterns of hana-ui float weaves, another Okinawan tradition; and ikat designs unique to Kijoka, many of which reveal the playful ways Taira and her associates have incorporated figures and forms seen in the everyday world around them. In her own works Taira often devised ikat patterns that would set off the natural, undyed earth tones of the ito-basho threads and thus reveal the skill not only of the weaver but of the yarn maker as well.

Popsicle motif ikat pattern; Yeddo hawthorn and Ryukyu indigo dyes; Taira Bashofu Studio, Heisei era (1989-2019). © Atsushi Higa / Photo Studio Tsuha |

Kijoka's textile artisans use plant pigments they prepare themselves to make their eye-catching ikat designs and stripes. The process of hand-binding the patterns directly onto the threads to create the resists is so exacting it staggers the mind. They fasten bundles of undyed yarns taut, parallel to the floor, and wrap them tightly with ties as specified by the design. The covered areas thus resist coloration when the skeins are plunged into the dye bath. What's striking is not only how precise the measuring and tying must be in order for the patterns to match up at all, but how it is even possible for the workers to keep the thousands of dyed threads perfectly aligned throughout all the subsequent steps of loom preparation -- pre-sleying, beaming, threading the heddles, sleying, and so on. The same challenge applies to keeping the warps aligned during weaving. A truly advanced weaver may sometimes intentionally shift or displace an ikat warp ever so slightly, to create subtle effects of movement in her design.

|

|

Flowers with classic ikat pattern on a yellow ground; Ryukyu indigo and garcinia dyes; Taira Bashofu Studio, Heisei era (1989-2019). © Atsushi Higa / Photo Studio Tsuha |

Among the many resist-dyeing techniques, ikat enjoys a long legacy in Okinawa, where it was transmitted from China and Southeast Asia in Ryukyu times. Most Okinawan women wove clothing for their families as a matter of course, and it's said that Kijoka weavers became increasingly adept at complex ikat designs sometime around the end of the 19th century, when interest in Okinawan textiles grew with the advent of the Meiji era. Soetsu Yanagi, founder of the Mingei (Folk Crafts) movement, visited Okinawa four times between 1938 and 1940. His survey of bashofu production sites together with textile designer Keisuke Serizawa led to Yanagi's 1943 publication of Bashofu monogatari (The Story of Bashofu), a handbound, limited-print essay extolling the appeal of the fabric and introducing Kijoka as its busiest center of production. A first-edition copy of this, along with Yanagi's handwritten manuscript, was on display.

|

|

|

|

|

Taira (center) and members of her studio pose with ito-basho plantains in the background; 2022.

© Atsushi Higa / Photo Studio Tsuha

|

In 1944 Taira was in Kurashiki, Okayama, working at a spinning mill that had been commandeered into an aircraft factory. With the end of the war she was offered an opportunity to stay on and hone her weaving skills, and was introduced to Kichinosuke Tonomura, a Mingei proponent and a dyer and weaver himself. He showed her Yanagi's essay, which strengthened her resolve to return to Kijoka and revive its bashofu tradition. Taira studied with Tonomura for the better part of a year, then returned to her home village in late 1946 to a situation that was bleak: whole fields of the ito-basho plants had been torched by U.S. military authorities because they were considered breeding ground for malaria-carrying mosquitos. Taira set to recultivating the native plantains, then organized local women, many of them widowed, into a weaving cooperative. Until sufficient fibers could be harvested, she wove with threads unraveled from army surplus blankets and tents. As Okinawans struggled to get their lives back on course under American control there was little demand for kimono cloth produced the olden way, but Taira persevered. She entered competitive exhibitions to establish recognition for bashofu and created new woven products, such as table mats and cushion covers, that the cooperative marketed to Americans on the island and to people on the main island of Honshu.

|

|

|

|

|

|

Left: Crossover top and pleated wrap skirt; Ryukyu indigo and Taiwan acacia dyes; Association for the Preservation of Kijoka Bashofu, 2012. Right: Nigashi bashofu kimono with tiny plaid pattern on a yellow ground; Ryukyu indigo and garcinia dyes; Taira Bashofu Studio, 2016. Both photos © Atsushi Higa / Photo Studio Tsuha |

Over the years I've had many opportunities to dive deeply into the lifework of Japan's Living National Treasures, and Toshiko Taira has always been my personal LNT rock star. Though the centenarian was, for obvious reasons, not at a talk event held in Tokyo for this exhibition last month, her spirit was very much present in the bevy of attendees decked out in bashofu kimono and obi. Despite the city heat, they looked cool and crisp in natural garments born beneath a subtropical sun and fashioned sustainably with grit, love and tenacity by hands determined to preserve and celebrate Okinawan culture.

Founded in 1917 by industrialist Kihachiro Okura, the Okura Museum of Art is Japan's first private museum. Along with the two new towers of the Okura Hotel completed in 2019, the classical Chinese building anchors this landscaped square near the U.S. Embassy in Toranomon. |

All photo permissions are courtesy of the Okura Museum of Art.

|

|

|

Susan Rogers Chikuba

Susan Rogers Chikuba, a Tokyo-based writer, editor and translator, has been following popular culture, architecture and design in Japan for three decades. She covers the country's travel, art, literary and culinary scenes for domestic and international publications. |

|

|

|