|

Focus features two in-depth reviews each month of fine art, architecture, and design exhibitions at art museums, galleries, and alternative spaces around Japan. |

|

|

|

|

|

Art Is an Explosion! Revisiting the Incendiary Creations of Taro Okamoto

Christopher Stephens |

|

Men Aflame (1955, National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo) |

At the time of his death in 1996, Taro Okamoto was probably the best-known modern artist in Japan.

High-profile projects like Tower of the Sun (1970) had helped him capture the public imagination, but it was Okamoto's willingness to play up the image of the crazy artist that made him a household name. With a wild-eyed stare, Okamoto appeared regularly on TV variety shows and commercials, advertising everything from video cassettes to watches and whiskey, and uttering catchphrases like "Art is an explosion!" Although this proved to be a winning formula for him professionally, his artistic legacy suffered as a result. Cue Okamoto Taro: A Retrospective (running through 2 October 2022 at the Nakanoshima Museum of Art, Osaka), the largest exhibition devoted to the artist's work since his death. The show aims to restore Okamoto to his rightful place in Japanese art history and reexamine his ideas for insight into present-day problems.

|

|

|

|

|

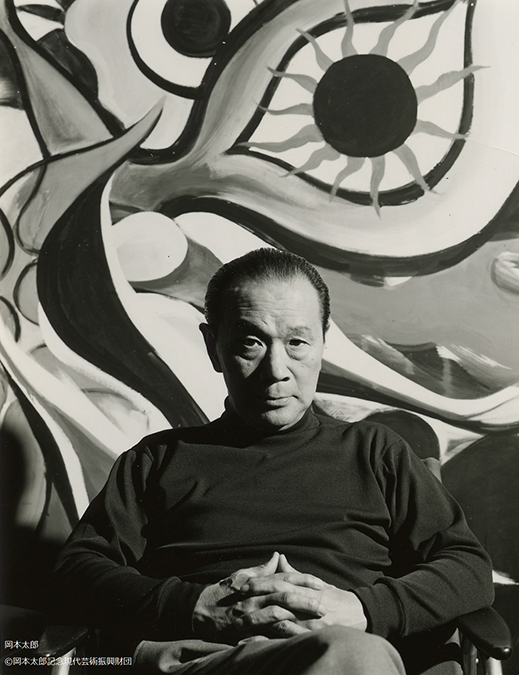

Taro Okamoto (Taro Okamoto Museum of Art, Kawasaki)

|

Born in 1911, Okamoto was the son of a cartoonist father, and a poet mother whose eccentric lifestyle did not always make her an ideal parent. Fascinated by painting from childhood, Okamoto enrolled in the Tokyo School of Fine Arts in 1930, only to quit the school six months later to accompany his parents on a trip to Paris. They went home, but Okamoto stayed -- for the next ten years. During this period he discovered abstraction and Surrealism, and moved in circles that included artists such as Pablo Picasso, André Breton, and the photographer Robert Capa and his partner Gerda Taro (who borrowed Okamoto's first name as her surname). He also studied with the ethnologist Marcel Mauss at the University of Paris and joined a secret society organized by the philosopher Georges Bataille. This heady period of art and ideas came to an abrupt end in 1940 when the Nazis invaded France. Okamoto returned to Japan, but was drafted not long after at the relatively advanced age of 30 and sent to the front lines in China before landing in a POW camp.

When Okamoto returned to Tokyo in 1946, he found that his house in Aoyama and everything in it, including all of the paintings he had made in France, had been destroyed in an air raid. Apart from three recently discovered paintings (included in this exhibition) that are thought to date from Okamoto's Paris years, the only extant works with links to this period are a few reproductions from the 1940s. Most prominent among these is Wounded Arm (1936/1949), a combination of abstract and figurative elements that depicts the muscular forearm of a woman ringed with purple bands, a large red bow for a head, and an oblique body that dissolves into the shadows.

|

|

Wounded Arm (1936/1949, Taro Okamoto Museum of Art, Kawasaki) |

Hurriedly trying to make up for the time he lost while in the army, Okamoto formed two avant-art groups and developed a theory of opposites known as taikyokushugi (polarism). This philosophy, which remained at the heart of Okamoto's work for the rest of his career, called for a synthesis of conflicting and contradicting elements, such as organic and inorganic, and rational and irrational. Meanwhile, a chance encounter with a pot from the Jomon era (c. 14,000 - 300 BCE) led Okamoto to explore ancient Japanese culture, providing him with a wellspring of motifs, including flames and flat faces with evocative expressions.

Although Okamoto is not generally associated with social commentary, he did attempt to convey his views through his art. The theme of nuclear catastrophe, for example, can be traced back to the early fifties. Like the film Godzilla (1954), Okamoto's Men Aflame was based on an incident in which a Japanese fishing boat was contaminated by radioactive fallout from a hydrogen bomb test carried out by the U.S. military at Bikini Atoll. In the painting, distressed boats and fish are visible beneath a maelstrom of eyes, snaky forms, and flashes of fiery light, suggesting the terrible moment of destruction at sea and the wider-reaching effects on humankind as a whole.

|

|

Myth of Tomorrow (1968, Taro Okamoto Museum of Art, Kawasaki) |

Okamoto firmly believed that art was something that should be freely accessible to everyone -- so much so that he initially resisted selling his works in the fear that they would end up in a dark cellar somewhere. This also explains his attraction to public art. In 1968, Okamoto was commissioned to make a 30-meter-long mural called Myth of Tomorrow (1968) for a proposed hotel in Mexico City. Inspired by Mircea Eliade's book The Myth of the Eternal Return, a favorite of Okamoto's, the scene, peopled with burning trees, swells of fire, and ghostly figures, depicts the human race overcoming nuclear disaster and carving a new future. In the event, the hotel went bankrupt before it ever opened, and the mural got lost in the shuffle. Following a decades-long search, led by Okamoto's wife Toshiko, the work was located in the suburbs of Mexico City in 2003 and returned to Japan. Since 2008 it has occupied a wall in Tokyo's Shibuya Station, looking down over a steady stream of passengers.

|

|

|

|

|

Tower of the Sun (1970, reference image), located in Expo '70 Commemorative Park, Suita, Osaka

|

Just prior to the Mexico project, Okamoto was hired to create a centerpiece for the Japan World Exposition, held in Osaka in 1970. Originally tasked with visually summing up the event's theme, "Progress and Harmony for Mankind," Okamoto was repelled both by the notion that science and industry would bring human happiness, and by the architect Kenzo Tange's rational plan for the Festival Plaza, located near the event's main gate. To counteract these forces, Okamoto opted for the irrational: A 70-meter-tall, bird-like creature called Tower of the Sun with a gold-colored metal face on its head, a sculpted face on its abdomen, and a black sun with blue and green rays radiating across its back. Inside the hollow concrete structure, Okamoto displayed the Tree of Life (a model appears in the exhibition), a brilliantly colored tree ornamented with nearly 300 small replicas of living organisms, from amoeba to human beings, that extend upward in evolutionary order. Today, Tower of the Sun, Okamoto's most significant achievement, stands tall as a symbol of Osaka.

If Taro Okamoto's imagery might seem a bit dated and overly repetitive, his social concerns and artistic passion burn as brightly as ever in this compelling exhibition.

All works shown are by Taro Okamoto. All images are copyright and courtesy of the Taro Okamoto Memorial Foundation for Contemporary Art.

|

|

|

Christopher Stephens

Christopher Stephens has lived in the Kansai region for over 25 years. In addition to appearing in numerous catalogues for museums and art events throughout Japan, his translations on art and architecture have accompanied exhibitions in Spain, Germany, Switzerland, Italy, Belgium, South Korea, and the U.S. His recent published work includes From Postwar to Postmodern: Art in Japan 1945-1989: Primary Documents (MoMA Primary Documents, 2012) and Gutai: Splendid Playground (Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, 2013).

|

|

|

|