|

Focus features two in-depth reviews each month of fine art, architecture, and design exhibitions at art museums, galleries, and alternative spaces around Japan. |

|

|

|

|

|

I Will Survive: Staying Alive with Art at Aichi Triennale 2022

Colin Smith |

|

Aya Momose, Jokanaan, 2019 |

It's become a pandemic cliché: three years ago seems like an eternity. The previous edition of the Aichi Triennale (held in Aichi Prefecture in central Japan) took place in the waning days of the innocent, mask-free era, though it faced trouble of another kind with right-wing outrage over a sculpture addressing the "comfort women" issue. The controversy contributed to minor changes -- Nagoya City has withdrawn financial support, never a king's ransom to begin with, and the Japanese name is now simply Aichi 2022, though the triennial schedule and English name are unchanged. But as this year's title, "Still Alive," tells us, the Triennale is alive and kicking.

On Kawara, One Million Years -- Past, 1970-1971, © Aichi Triennale Organizing Committee, © One Million Years Foundation |

Amid the uproar in 2019, that Triennale's title, "Taming Y/Our Passion," took on a bitterly ironic tinge. There's irony in the new title too, though intentional, in that the fifth edition is the first to include non-living artists, and the phrase "Still Alive" is quoted from one of them. Aichi native On Kawara (1932-2014) sent around 900 telegrams to acquaintances worldwide between 1970 and 2000, each announcing I AM STILL ALIVE. Many are arrayed in glass cases here, and as with Kawara's iconic Date Paintings, their number and subtle variations (telegraph company logo, paper size) amid endless sameness convey both the transience of a single day and the weight of an entire life. Then again, a life is a blip in geological time, as illustrated by another Kawara production, One Million Years. Here he typed out the numbers for the million years on either side of the present, and the resulting bound volumes are unexpectedly massive and numerous, while one's own lifespan might fit on a single page. A recording of voices reading the years has a hypnotic, sheep-counting quality.

|

|

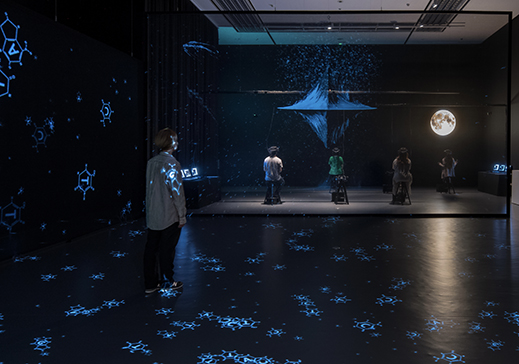

Laurie Anderson and Huang Hsin-Chien, To The Moon, 2019 |

Kawara's ostensibly mundane yet indefatigable projects exemplify a shift in the Triennale's focus, from contemporary art as something "extraordinary" to something woven into the fabric of everyday life. Current practitioners of serialism are represented here by Roman Ondak, whose tree cross-sections with rings indicating historical events are being added to a wall daily during the Triennale's term, and by Mit Jai Inn, a few of whose 365 flexible fabric pieces are offered free of charge each day to visitors, who are asked to upload photos of them on social media. There is a fair amount of conceptually oriented work, but the tone remains lively thanks to the well-balanced interspersion of pieces with high entertainment value. One highlight, Laurie Anderson and Huang Hsin-Chien's VR and video installation To the Moon, requires advance reservations for the 15-minute VR experience.

Tomomi Adachi, MAVOtek Part V, 2022 |

Tomomi Adachi, 3D Printed Poetry, 2017-2022 |

As with any art festival, the greatest pleasure is discovering new (to this writer) faces, and among the approximately half-and-half lineup of foreign and Japanese artists, young and mid-career standouts from Japan include two multimedia practitioners, Tomomi Adachi and Aya Momose. Adachi presents MAVOtek Part V, an immersive experience of phonetic synesthesia in which the visitor, inside a translucent cube, is bombarded with high-speed clips of sound from speakers on all sides and flashing images of textual characters and a giant mouth uttering phonemes. The title references the early 20th-century Japanese avant-garde group MAVO. Momose's show-stopping two-channel video Jokanaan enacts a scene from the Richard Strauss opera Salome where the titular character addresses Jokanaan (a.k.a. John the Baptist) in a frenzy of passion, with blood-drenched hands. The physical man on the left screen, wired with sensors, moves and lip-synchs, while the eerie all-white computer-graphic maiden on the right moves accordingly via motion-capture technology. Resembling a musical interlude from a CG-animated blockbuster in full nightmare mode, the piece mesmerizes from start to finish and leaves questions about what it all means.

|

|

Sayako Kishimoto, 21c. Erotical Flying Machines -- A Trip to the Galaxy (Original Drawing), 1983 (detail) |

Sayako Kishimoto (1939-1988) was a radical artist and performer, undeservedly under-remembered, who now gets her due in her hometown of Nagoya. Paintings of cosmic battles between laser-eyed cats, gorillas in fantastical landscapes, and insects in numinous geometric spaces are accompanied by photos of her actions, which included destroying her works by painting over them (and herself) in public, and running for a parliamentary seat as a candidate of the Zatsumin-to (lit. "Miscellaneous People's Party," champions of the disenfranchised). In a televised campaign speech she described herself as a messenger from hell, and in the early 1980s she had already declared herself a 21st-century witch. The 21st century could use more of the kind of energy Kishimoto seems to have brought to every endeavor.

Yuki Kihara, A Song About Samoa -- Fanua (Land), 2021 |

The Triennale's main venue is the Aichi Arts Center in Nagoya City, but it occupies three other venues around the prefecture as well. Elsewhere in Nagoya is the picturesque Arimatsu district, known for Arimatsu-Narumi shibori (tie-dyeing, but not the hippie kind), where historic houses and workshops, many appearing unchanged since the Edo period (1603-1867), are the site of a dozen art exhibits (wear shoes that easily slip on and off!). Many, including the aforementioned works by Mit Jai Inn, relate in some way to textiles. Five paintings on kimono using the traditional Samoan dyeing technique of siapo, by Yuki Kihara, an artist from Samoa with Japanese ancestry, are visually stunning and charming while conveying sobering messages about globalization and environmental degradation.

Chiharu Shiota, Specimen Room, 2022 |

Tokoname and Ichinomiya are cities in other parts of Aichi Prefecture, accessible by train from Nagoya Station in about 25 and 40 minutes respectively. Ichinomiya, like Arimatsu, has a historic connection to textiles, and like many mid-sized post-industrial cities it also has disused spaces that offer opportunities for large-scale installations. The Former Ichinomiya City Ice Skate Rink, shuttered earlier this year, houses Anne Imhof's video and sound piece Jester, while the Former Ichinomiya Central Nursing School is the site of works by more than ten artists or groups. One installation of note is Chiharu Shiota's Specimen Room, where she engulfs anatomical specimens in her signature networks of thread.

Ryoji Koie, Chernobyl Series, 1989-1990 |

Tokoname is well known as one of Japan's six ancient pottery-producing regions. The INAX Museums complex there features Ryoji Koie (1938-2020), who was born in Tokoname and took ceramics in a more avant-garde direction with works like Chernobyl Series (1989-1990) -- which has new layers of import in light of recent news about Russian strikes on nuclear power plants in Ukraine. Another venue in the city, the Former Earthenware Pipe Factory (Maruri-Toukan), showcases several artists including Chicago-based Theaster Gates, who has been deeply engaged with urban revitalization and has frequently visited this region since doing a residency in Tokoname in 1999.

Kazufumi Oizumi, Movable Bridge/BH 5.0, 2022 |

It takes at least two days, and a longer review than this one, to do justice to an art festival with multiple venues and nearly 100 exhibitors. The curators encouraged overseas artists to visit the exhibition sites in person, and approximately half managed to make the trip despite trying circumstances. The Aichi Triennale succeeds in feeling like an international collaborative endeavor, not just an oversized exhibition as can be the case with biennial- and triennial-style events. There is a sense of interaction with works like the very slowly moving sculptures of Robert Breer (1926-2011) and Kazufumi Oizumi's minimalist glass and metal Movable Bridge/BH 5.0, which descends six times per hour in the Aichi Arts Center lobby to let one person at a time cross it. While waiting, you can enjoy doing nothing -- sometimes that's the best way to remember you're still alive.

All images © Aichi Triennale Organizing Committee except where otherwise noted. All photos are installation views at Aichi Triennale 2022, by ToLoLo Studio. |

|

|

Colin Smith

Colin Smith is a translator and writer and a long-term resident of Osaka. His published writing includes the travel guide Getting Around Kyoto and Nara (Tuttle, 2015), and his translations, primarily on Japanese art, have appeared in From Postwar to Postmodern: Art in Japan 1945-1989: Primary Documents (MoMA Primary Documents, 2012) and many museum and gallery publications in Japan.

|

|

|

|