|

Focus features two in-depth reviews each month of fine art, architecture, and design exhibitions at art museums, galleries, and alternative spaces around Japan. |

|

|

|

|

|

The Future Is Past: Revisiting the Art of 1972

Christopher Stephens |

|

Tadanori Yokoo, Glorious Beatles Festival (Daimaru) (1972, The National Museum of Art, Osaka collection) |

Choose any year in history and you're bound to come up with a few milestones, be they glorious or tragic. The conceit of the exhibition Back to 1972: How Japanese Contemporary Art Looked 50 Years Ago is that one year in particular, 1972, was a defining moment in Japanese art. The show, on view at the Otani Memorial Art Museum, Nishinomiya City through 11 December, also commemorates, with minimal fanfare, the institution's own 50th anniversary.

Opened on November 3, 1972, the museum owes its birth to Takejiro Otani, the president of the Showa Electrode Corporation, who donated his private residence, sprawling garden, and collection of modern yoga (Western-style paintings), Nihonga (Japanese-style paintings), and French paintings to the city of Nishinomiya to promote art appreciation in the area. As the museum concept was still relatively new to Japan (the Tokyo National Museum, considered to be the oldest museum in the country, opened exactly 100 years earlier in 1872), it was often wealthy businessmen like Otani who brought art to the general public.

Although this exhibition nominally celebrates the Otani's anniversary, the works on display are almost entirely on loan from other Kansai-area museums. This perhaps reflects the fact that when the museum opened, it was more concerned with art of the past than of the present. An introductory section provides background information on notable events that occurred around the country in 1972. The Winter Olympics were held in February in Sapporo (the games had originally been slated for the city in 1940 but were cancelled due to the war) followed soon after by an incident in which members of the United Red Army seized a hostage at a mountain lodge in Karuizawa, Nagano Prefecture, and killed two police officers in a standoff that lasted for over a week. In May, Okinawa reverted from the U.S. to Japan, and the next month, W. Eugene Smith published his photo essay "Death-flow from a Pipe" in Life magazine, alerting the world to a horrendous neurological disease caused by industrial pollution in the coastal city of Minamata, Kumamoto Prefecture. In addition to some of Smith's photographs, the displays include iconic examples of Japanese graphic design such as Kiyoshi Awazu's poster for a Kobo Abe-penned stage production titled Life-saving Method, and Tadanori Yokoo's poster for a Beatles exhibition at the Tokyo branch of the Daimaru Department Store.

|

|

Keiji Uematsu, Construction of Space Relation -- Tree / Man / Rope II (1972/2016, collection of the artist) |

With only a handful of galleries willing to show their work, cutting-edge artists of the early '70s relied on events like the Kyoto Biennale, the inaugural edition of which was held at the Kyoto Municipal Museum of Art in 1972, for wider exposure. In photos of the show, the museum appears to be filled with the detritus of a former tenant. Huge sheets of paper, dozens of copies of the Mona Lisa, and a sea of wrinkled-up newspapers cover the floors, obstructing the walkways and entrances. Where there is open space, it is dotted with painted arrows and strips of masking tape. Other rooms are filled with boards propped up against the walls, and huge oval rings constructed of lightweight wood through which viewers must walk to get to the other side. The objective here was clearly to subvert the conventional display format and break free from the white cube. Of special note in this regard is the work of Kobe-born sculptor Keiji Uematsu (b. 1947), who is today esteemed for gravity-defying assemblages of red cones perched on round stones, and metallic trees with stunted branches floating off the edge of a table. At the Biennale, however, Uematsu turned his own body into a sculptural element. In the first of two works, titled Construction of Space Relation -- Tree / Man / Rope I and II, each made up of nine black-and-white photographs, Uematsu tied a rope to the upper limb of a tree as he slowly leaned back toward the ground, and began walking up the trunk until he was hanging upside down with his body nearly parallel to it. In the second work, Uematsu started out by lying face-down on the ground with the rope tied around his ankles and gradually drew himself erect by performing a handstand. Then, after removing his hands and standing completely upright (downright?) with his head on the ground, he propelled himself away from the tree. What initially seems to be the record of a performance piece is actually a series of transitory sculptures based on the relationship between two living materials.

|

|

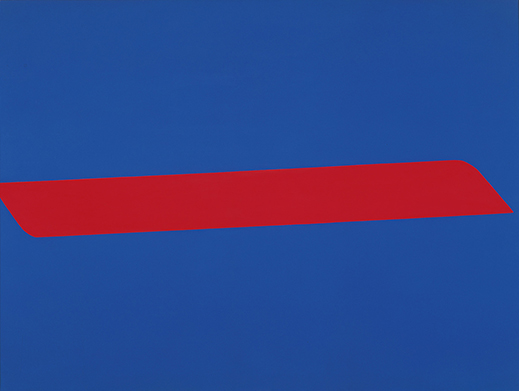

Jiro Yoshihara, Work A (1971, Nakanoshima Museum of Art, Osaka collection) |

1972 was also the year that Gutai, Japan's premier (though at the time not widely recognized) avant-garde art group, came to an end. Gutai leader Jiro Yoshihara (1905-1972), who oversaw his family's vegetable oil business while pursuing a career as a painter, collapsed and later died of a subarachnoid hemorrhage that February. Not long afterward the group's members elected to go their separate ways. The exhibition focuses on Yoshihara's own works, which have often been overshadowed by the flashier efforts of his younger charges, and those of Gutai's lesser-known members, many of whom joined the group after 1965. Along with some of Yoshihara's watercolor sketches, there is one of the artist's trademark circle paintings, a motif with all the immediacy of a Zen enso painting but executed with greater care and exactitude. As Yoshihara readily admitted, the circles were above all a matter of convenience. Having a go-to motif saved him from casting around for a subject and focused his mind on the task at hand. Yet he did occasionally stray from the path and depict things like the bend in a circle or a straight brushstroke in flat two-tone works that echo the hard-edged paintings of the early '60s, and are a million miles away from his Surrealist-influenced figurative paintings of the 1930s.

|

|

Tomio Miki, Ear (1972, The National Museum of Art, Osaka collection) |

The fourth part of the exhibition is devoted to several key artists of the period, including the photographer Shigeo Anzai (1939-2020), whose beautifully crafted pictures document artists' working methods, exhibition views, and performances that would have otherwise been lost to time. Here, Anzai captures the sculptors Lee Ufan (b. 1936), Nobuo Sekine (1942-2019), and others associated with the Mono-ha movement, which combined unadulterated materials like glass, stone, and paper to plumb their individual essence and explore the complex relationship between the natural and the artificial. Tomio Miki (1937-1978) was a sculptor of an entirely different kind. After developing an obsessive interest in the human ear in 1963, Miki devoted himself to casting the form in aluminum and brass until his sudden death at 40. These disembodied ears (almost always the left one) range from life size to 170 centimeters from top to bottom. At a larger scale, the motif's curves, ridges, and inner depth are accentuated by the silver color of the metal and varying degrees of roughness and smoothness, manifesting something that, like a real ear, is a world unto itself.

|

|

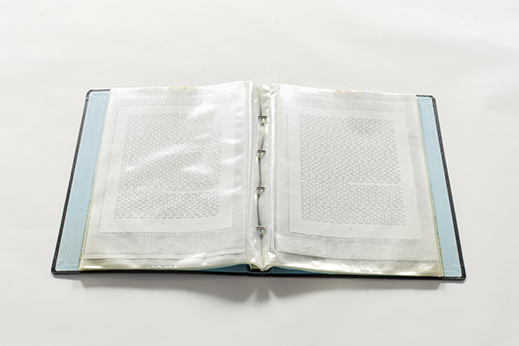

Jiro Takamatsu, The Story (1972, Museum of Contemporary Art Tokyo collection, © The Estate of Jiro Takamatsu, courtesy of Yumiko Chiba Associates) |

The last major trend of the 1970s covered in the exhibition is the rise of printmaking as a medium for fine art. Due in part to technical innovations such as silk screening and photoengraving, the period is seen as a golden age of prints, giving rise to numerous international exhibitions, galleries, and magazines that specialized in the genre. Woodblock prints, which had once been a mainstay of Japanese culture, had largely faded from the art world by the late 19th century, but the relative ease of 20th-century methods made printmaking a natural for younger artists. There was also a freshness about the colors and forms that was impossible to replicate with the hand, giving expressions in print a special vibrancy. At the same time, there were controversial works like Jiro Takamatsu's The Story, which called print- and art-making into question. The work consists of a file containing Xerox copies of page after page of seemingly random groupings of typed letters that Takamatsu (1936-1998) had arrived at through a set of undisclosed rules. Winner of the International Grand Prize at the 1972 International Biennial Exhibition of Prints in Tokyo, The Story punches a hole in the art world's overly precious view of itself while demystifying the printing process.

Back to 1972 functions as a snapshot of one year as well as a compendium of the decade as a whole, showing us where Japanese contemporary art has been and reminding us where it's at now. The trip there is both a pleasure and an education.

All images provided by the Otani Memorial Art Museum, Nishinomiya City.

|

|

|

Christopher Stephens

Christopher Stephens has lived in the Kansai region for over 25 years. In addition to appearing in numerous catalogues for museums and art events throughout Japan, his translations on art and architecture have accompanied exhibitions in Spain, Germany, Switzerland, Italy, Belgium, South Korea, and the U.S. His recent published work includes From Postwar to Postmodern: Art in Japan 1945-1989: Primary Documents (MoMA Primary Documents, 2012) and Gutai: Splendid Playground (Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, 2013).

|

|

|

|