|

Focus features two in-depth reviews each month of fine art, architecture, and design exhibitions at art museums, galleries, and alternative spaces around Japan. |

|

|

|

|

|

Back to Nature: Stones and Plants Take Center Stage in Shiga

Colin Smith |

|

Left to right: Seii Inoda, Stream, 1960; Kenneth Noland, Cadmium Radiance, 1963; and Constantin Brancusi, Bird in Space (partial view), 1925. Note the different types of stone in Brancusi's pedestal. Installation view, photo by Atsuhiro Miyake |

Like nonfiction books in the English-speaking world these days, museum exhibitions in Japan, especially thematic ones, tend to have lengthy subtitles that explain what they're all about, but not this one. Stones and Plants at the Shiga Museum of Art focuses on those two elements of the natural world from multiple angles -- as subject matter, as materials, as sources of inspiration, in media ranging from painting to basketry to video -- and the all-too-rare decision to avoid an expository subtitle (like "Exploring the Ways We Engage with Nature Through Art," say) is an excellent one. It's better to go into a show like this one curious (stones and plantsc?) and without preconceptions.

Soshi Matsunobe, My Stones (partial view), 2011, and Isamu Noguchi, Childhood, 1971. Installation view, photo by Atsuhiro Miyake |

The exhibition features 85 works from the museum's collection, including several by two younger artists specially invited to contribute. It starts with a room containing Isamu Noguchi's Childhood (1971), an imposing yet pleasingly rounded and nubbly biomorphic sculpture dramatically lit to showcase its texture. This is one of several works accompanied by explanations, courtesy of the nearby Lake Biwa Museum, of their materials, in this case Aji granite. Knowing that you're looking at igneous rock from the Cretaceous period quarried in Kagawa Prefecture, where Noguchi had a studio, adds a new dimension. In the same gallery is one of My Stones (2011) -- highly realistic rocks fashioned from cement and distributed throughout the exhibition, certainly another case where knowing the material adds to one's appreciation. Made by Soshi Matsunobe (b. 1988), one of the aforementioned emerging artists, they really look like natural stones, producing a this-is-not-a-pipe state of cognitive dissonance when one learns they are not. For details (in English) on this work, and all the others in the show, be sure to pick up one of the generously information-packed booklets at the entrance.

|

|

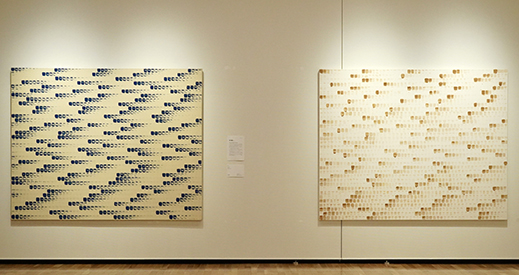

The mineral and vegetable kingdoms: Lee Ufan, From Point, 1976, and Tsuyoshi Ozawa, Soy Sauce Art (Lee Ufan), 2004. |

Though it's not obvious to the eye, stones figure as materials in many of the paintings here. Nihonga (Japanese-style painting) is often done with mineral pigments and animal-based glue, and a standout in this show, the bold, almost abstract Stream (1960), by Seii Inoda, makes the mineral kingdom its subject as well in the form of rocks in a riverbed. Cadmium Radiance (1963), a geometric abstraction by color-field painter Kenneth Noland, is aglow with the brilliant yet toxic titular substance, and a painting from Lee Ufan's meditative series From Point (1976) also derives its rich monochromatic color and grainy quality from mineral pigment. Speaking of materials, Lee's work shares a wall with Tsuyoshi Ozawa's replication of it using a plant-based liquid, Soy Sauce Art (Lee Ufan) (2004), also part of a series. Ozawa is known both for working with food and for dealing satirically with regional identity, as in his ongoing project Vegetable Weapons. The soy sauce piece reads as a tribute rather than a parody; hanging next to the original, it highlights the rigorous discipline and control of breath and body that Lee applied to the simple act of dipping a brush in pigment and dabbing it until the paint fades, then reloading it. Not to knock Ozawa's homage, but -- while Lee's work might appear to be the sort about which people say "I could do that" -- don't try this at home.

|

|

Shuji Okada, Waterscape 15, 2001. |

Plants are of course the source of many art materials, but in this exhibition they feature more prominently as subjects. Shuji Okada's black-and-white oil paintings of vegetation and water are photorealistic enough to cause a double take in the same manner as Matsunobe's "stones." There are several works of Art Brut (a.k.a. outsider art), an area of specialization for museum director Kenjiro Hosaka, focusing on fruits and vegetables: persimmons exuberantly rendered by self-taught artist Shisuko Tohmoto when she was 88, a cluster of works from outsider artist Masao Obata's lifelong project of depicting a fertile utopian world in colored pencil on cardboard, and the remarkable Onion (1992) by Tetsushi Iwashita. Resembling geological strata, this dynamic, colorful closeup of a cross-section of that fragrant bulb is the work of a man who lost almost all functioning of his right brain in infancy, then miraculously managed to compensate with his left and become a prolific artist.

|

|

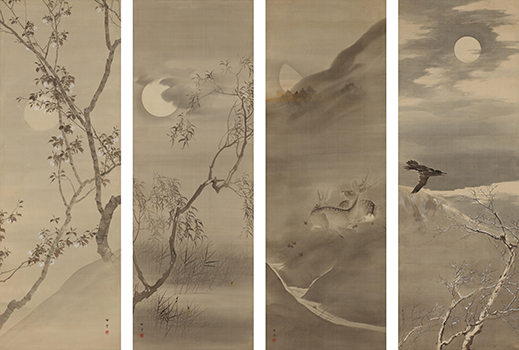

Chikudo Kishi, Moon of the Four Seasons, 1877-1886. |

Plants are, of course, a central theme in traditional Japanese painting. Chikudo Kishi's Moon of the Four Seasons (1877-1886) is kind of an apotheosis of the classical kachofugetsu ("flowers, birds, wind, moon") aesthetic, and while it is not large, the delicacy of the painting on four silk screens makes it perhaps not surprising that it took a decade to complete. Bairei Kono was an educator as well as a painter, and many of his dense and detailed paintings could function as botanical and zoological illustrations, though Matsutake Mushrooms (late 19th century, year unknown), featured here, has a lighter and brushier touch.

|

|

|

|

|

A taste of autumn: Bairei Kono, Matsutake Mushrooms, late 19th century.

|

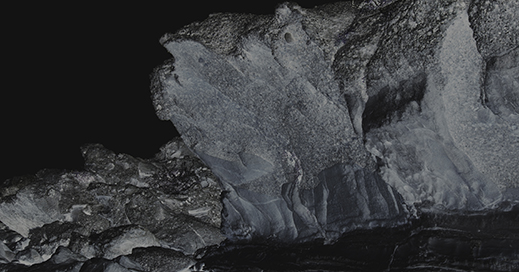

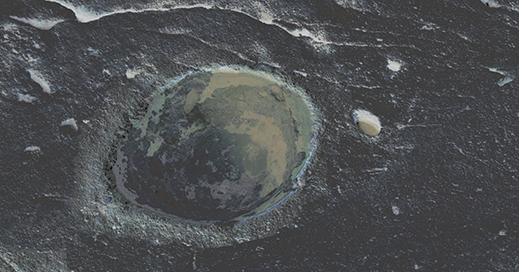

Stones and plants come together in a pair of videos by Kanako Azuma (b. 1991), one of the two invited emerging artists. The Voice of Each Body (2022) focuses on the natural scenery of the Boso Peninsula, east of Tokyo Bay, parts of which are highly industrialized and urbanized while others remain in a primal state. The work endeavors, in the words of curator Atsuhiro Miyake, "to listen to the voices of memories etched in the strata, stones, and residues in the place and in the earth," with results that at times recall the unpeopled opening sequences of the non-narrative 1982 film Koyaanisqatsi. The other video piece, Eternal beloved (2022), goes inside an orchid-breeding greenhouse that looks more like a state-of-the-art laboratory. The precision equipment and climate control that go into raising these hothouse flowers point to timely questions about the boundaries between natural and artificial life.

|

|

|

|

|

|

Kanako Azuma, two stills from The Voice of Each Body, 2022 (photos by Atsuhiro Miyake), and (at bottom) a still from Eternal beloved, 2022. |

Next to the darkened video screening room is a rest area where you can look out on a lovely arrangement of plants and stones in the traditional Japanese garden next door. The Shiga Museum of Art is certainly ideally situated for an exhibition with this theme. The idea for the show, according to an introductory text, grew out of a conversation between director Hosaka and curator Miyake. Musing about "the ladder of existence" (from mineral to vegetable to animal) as presented in classical museums of natural history, they wondered how this theme might be applied to Shiga Prefecture, and drew inspiration from two local nature lovers, mineralogist Kiuchi Sekitei (1725-1808) and avant-garde tanka poet and botany enthusiast Kunio Tsukamoto (1920-2005). These two figures, while not showcased in the exhibition, served as lodestars for its curation.

The show's final gallery contains studies for unrealized works of massive scale: Christo and Jean-Claude's Surrounded Islands / Project for Biscayne Bay, Greater Miami, Florida (1981) and Nobuo Sekine's Project Kremlin (1977). The former involves applying human agency to natural terrain with the artists' trademark practice of wrapping, while the latter conversely proposes introducing nature into a human-made space (specifically, suspending a giant boulder, kept in precarious equilibrium by another giant boulder, from a column in front of the Kremlin). Given the current situation in Russia, realization of Sekine's delicately balanced project seems both more unlikely and more apt than ever. As a coda to the exhibition, wander outside, where two of the sculptures on permanent view fit nicely into the show's theme and let you appreciate art amid nature. With life slipping out of balance all around us, it's good to think that at least stones and plants will endure.

|

|

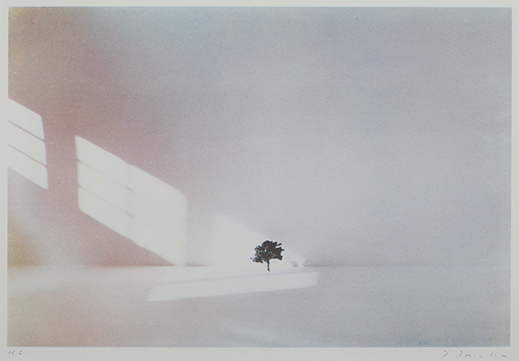

Takashi Tanaka, Tree, 1977. The artist made plaster casts which he then photographed and silkscreened, giving obviously impossible scenes a persuasive quality of reality. |

All images courtesy of the Shiga Museum of Art. |

|

|

Colin Smith

Colin Smith is a translator and writer and a long-term resident of Osaka. His published writing includes the travel guide Getting Around Kyoto and Nara (Tuttle, 2015), and his translations, primarily on Japanese art, have appeared in From Postwar to Postmodern: Art in Japan 1945-1989: Primary Documents (MoMA Primary Documents, 2012) and many museum and gallery publications in Japan.

|

|

|

|